Posts tagged Second Life

Undersea Observatory Available for Download and Featured at VWBPE

3Version 0.9 of my Undersea Observatory for OpenSim is available for download. It’s available as a standalone OAR, which can be imported into your own OpenSim server, or another OpenSim host like Kitely. There’s also a standalone version packaged with Sim-on-a-Stick that you can basically just unzip and run. I’ve noticed a few bugs already in the sim, which I’ll fix. The permissions seem to be incorrect for the mini-submarine, so I don’t think visiting avatars can use it. Somehow my install got corrupted, and I can’t even modify the submarines, so I’ll have to figure something out. And I’m still working on scripting the squid and the kiosks, so I removed those from this version. They will be added in the 1.0 release.

I have a poster session exhibit set up at the VWBPE 2012 Conference, too, which is running from March 15-17: http://maps.secondlife.com/secondlife/EduCommons%20Bravo/84/41/26

UPDATE 2012-03-16: My exhibit was nominated for the award for Best Example of Educational Practices in a Virtual World!

Thoughts on Student Safety and Using OpenSim for Education

1OpenSim is making headway as a viable alternative to Second Life. About 98% of the functionality of Second Life is present in OpenSim. The remaining 2% primarily deals with vehicle physics. Although it is still considered “alpha” software, OpenSim hosting is sold, and teachers, students, and businesses are taking advantage. The alpha status reflects more on the rapidly changing nature of the virtual world market, than the stability of the software itself. Microsoft and IBM have some backing in it. Intel operates its ScienceSim experiments with OpenSim, and has made headway in providing models for ubiquitous shareable content and massive user connections.

There are definitely some measures being taken to address educators’ needs. The Jokaydia and 3rd Rock Grids have been around for several years, and they are largely education-oriented. Last year, Firesabre launched its own Starlight Grid, which provides private hosting for educators. And Kitely is starting to establish itself as the premiere third-party choice for educators, and provides the option for making user-created regions private. However, as hypergridding becomes more stable and common, this can be the vehicle to unite different grids into a single education-related hypergrid. The common “education hypergrid” should blend the most relevant content for students and teachers into a singularly accessible virtual space. There should never be any reason for a teacher or student to log out of their viewer and log back into another grid with a whole new avatar. But we need to think about how to make such a hypergrid suitable for students, especially K-12 since there’s often a litany of additional laws and policies governing online interactions and access for them.

A few thoughts and ideas come to mind:

- It is more productive to include students rather than solely use teachers to create content. Many teachers already do this, since with their often beyond-full-time jobs they simply don’t have the time to both learn the skills needed for building in a virtual world, and actually construct the content alone. We should use the skills of the young tech-savvy generation, and develop constructionist class projects that appeal to our students.

- Activities should directly tie in with the curriculum. This is rather obvious, but it would be useful if virtual world activities were tagged with the relevant standards and/or objectives they address. This way, others in the same state, province, or country can find relevant material, without having to wonder if it actually addresses the necessary learning content or is just another topical sim.

- To address safety issues, different approaches have been taken. I mentioned above how FireSabre and Kitely provide private regions. For educators, they don’t want inappropriate content to drift in, or outside trolls to visit the region and cause havoc while students are using it. While securing a sim for exclusive private access is well-intentioned, they miss out on the community-produced educational content. Whether this is on Second Life, OSGrid, or any other virtual world system, a significant strength of the virtual world is in its shared content. We should avoid having to recreate the wheel each time.

- One solution could be to script a session monitor. Those who wish to join the education hypergrid can be required to place a script inside each region which connects to a server and monitors participants. Teachers who wish to use a particular region (or group of regions) for learning but are worried about others coming in and disrupting the class can reserve a session, and either enter their students’ avatar names, or have the students sign up themselves. The script would monitor anyone entering or currently in the region and kick out anyone not registered for the session. A publicly viewable calendar in the regions and on the web would let others know what time slots are open.

- We need to provide a venue for coordinating with educators and organizations who are considering investing actual time or money in the development of a sim. If similar goals and objectives can be identified, pooling resources together may help alleviate the burden for all parties involved.

-

Regions such as the "Foul Whisperings, Strange Matters" Macbeth sim in Second Life could be added to an educator-maintained whitelist so the viewer knows it's student-appropriate

One solution to the problem of inappropriate content and the ability to provide a safe gateway to Second Life for students 16+ may be to build a custom viewer that uses whitelists. Ideally based on Viewer 2/3 (e.g. Kokua and Firestorm are two viewers being developed off this branch), it would access a server-maintained whitelist of regions appropriate for students. Anything not on the whitelist would not be accessible from the viewer. This can cross over to OpenSim as well. Though some regions on different grids may be “education-appropriate” and suitable to be hyperlinked to, other regions may not be. A mechanism in the viewer could prevent teleporting to regions that aren’t specifically part of the education hypergrid. This doesn’t prevent the usage of other viewers from bypassing these client security measures, but it’s still one measure that could help, and may meet the security policies of many schools and districts. Another option is to implement a teleport-restricting module on the server side so it limits access to educational regions, but since OpenSim is still in alpha, requiring it be included in all upgrades may be inconducive, unless a separate fork of OpenSim is made (much like OSGrid or Diva Distro). - When appropriate, content should be Creative Commons-licensed. This isn’t entirely necessary, and I believe there is tremendous value in reinforcing the commercial OpenSim goods market. But any CC content could be provided as OARs and IARs (compressed archives of OpenSim content), so it can be installed on private servers. Direct links to OARs and IARs should be posted inside the regions themselves, when possible.

- We should create an open, zero-cost (for the end user) conference region. This can be accessed from anywhere in the hypergrid, and can be reserved for school events or professional development as needed.

Hopefully I’m not too far off base with some of these thoughts. I believe as we move forward it will become increasingly important to standardize how educational simulations are maintained so they can meet the policies and safety standards of most school systems.

This article was reprinted in Hypergrid Business.

A Theoretical Model for Virtual Worlds in Weber School District

0 I’d like to implement virtual worlds in Weber School District. Hopefully, I’m in a position to actually steer things in this direction, and make it happen and get beneficial results. My concern with the implementation is that Second Life itself has a minimum age of 16. Great for high school kids, but it leaves out anyone younger. Plus there’s safety and security policies in place that make it complicated. However, if we used OpenSim or another third party, self-hosted virtual world solution, we could have complete control over the server, albeit at a loss of the rich content in Second Life. In essence, we’re starting from scratch.

I’d like to implement virtual worlds in Weber School District. Hopefully, I’m in a position to actually steer things in this direction, and make it happen and get beneficial results. My concern with the implementation is that Second Life itself has a minimum age of 16. Great for high school kids, but it leaves out anyone younger. Plus there’s safety and security policies in place that make it complicated. However, if we used OpenSim or another third party, self-hosted virtual world solution, we could have complete control over the server, albeit at a loss of the rich content in Second Life. In essence, we’re starting from scratch.

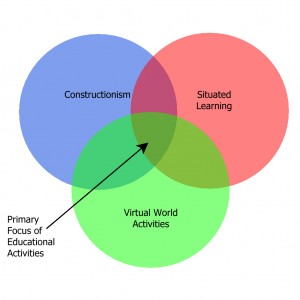

This is why we must adopt a constructionist approach when addressing virtual world instruction. Constructionism is a form of constructivism where artifact creation is the product of learning. The way I see it, students themselves should be the primary creators of the content and build the sims, under the direction of the teacher. Lessons should be designed that teach the intended content while the student is in the process of constructing, and the lessons should be designed to support a situated learning framework. Identifying an appropriate context for the learning, and focusing on collaborative activities is important.

When implementing constructionist activities in Second Life or OpenSim, it’s crucial that the teacher facilitates and provides consistent scaffolding support to the students, especially when there are varying skill levels. This takes constant observance of the activities, and at no time should a teacher stand on the sidelines, but be actively engaged in the process. With this type of activity, it is important that the instructor be continually and intimately aware of everything going on, to facilitate the experience. During the activity, the teacher should consistently provide help or suggestions that ensure a smooth and effective learning experience.

Identifying the types of activities that support the constructionist mode of learning inside the virtual world will enable us to find the right balance that fosters optimal learning opportunities. I certainly realize that there are many other ways to learn in a virtual world besides building content. But this is a necessary model for Weber School District, due to our existing infrastructure.

The learning activities that should be implemented, necessarily should adopt this “situated constructionist” approach. This way, especially with the forthcoming mesh abilities of Second Life and OpenSim, drafting students could import their buildings into Second Life. 3d animation students could import their characters and models. Programming students could learn the Linden Scripting Language and code the simulations. The virtual world implementation will be autonomous, and draw upon effective learning theories to guide its educational development.

Related articles

- Why Open Sim will Dominate Virtual Worlds in Education (coolcatteacher.blogspot.com)

- Reflections on Immersive Virtual Learning (weber.k12.ut.us)

- Teaching and Learning Options in the Virtual World (gridjumper.net)

Virtual Ability

0When we talk about teaching in virtual worlds, we’re not just talking about an extension of classroom practices in a virtual setting, but adopting a completely different paradigm and approach to instruction. One important consideration that can’t be overlooked is how the students react in the virtual setting; the teacher must be aware of and sensitive to their needs.

It can be astonishing to some to learn that accessibility is a very real issue in virtual worlds. The Virtual Ability Island in Second Life illustrates how different people with different disabilities react to the virtual world setting. In some cases, citizens who are wheelchair-bound in real life are not comfortable walking around in the virtual world setting, and may opt to roll around in a modeled wheelchair instead. It’s remarkable how some people identify themselves in certain ways, and these aspects become an integral part of their self-image.

In other cases, virtual worlds are able to break down the barriers some feel in the real world. Those with speech impediments may find it easier to communicate through typing. Different assistive tools available on the computer can ease the transition into a virtual world setting, and provide a level of comfort that facilitates an improved learning experience for the student. Some of these may include speech recognition software, text-to-speech applications, and alternative user interfaces.

Virtual worlds are a fairly new technology for educators. Best practices are constantly being developed, studied, analyzed, evaluated, and revised, and the sophistication of this technology will only increase with time. As with any technology, it is evolving and changing rapidly, and the greatest challenge will likely be trying to keep up with the latest advances. It is ultimately the teacher’s responsibility to be aware of their students’ unique needs and tailor instructional measures to provide the optimal experience for the learners.

Geo Quest

0Here’s a simple “culture quest” for Geo Island, a region in Second Life dedicated to the study of geology. Interactive models, slideshows, and informational posters are available to guide students through topics relevant to earth science study.

http://maps.secondlife.com/secondlife/Geo Island/140/62/504/

Begin your journey by heading north. Read all the posters you see. What are silicates? What percentage of minerals are silicates, and how much of the Earth’s crust is made up of them? What are the 7 listed types of crystal systems?

After you’ve explored this area, head to the western part of the region. Find the model of “Normal Faults” and touch it to see what happens. Look at the representation of rock layers. What is the difference between DIP and STRIKE?

Go to the far southeast area of the region. View all the slides. Describe the types of weathering. Where was the magnetic north pole 500 million years ago? On the Mohs Hardness scale, which mineral is listed as the softest, and which is the hardest?

Social Presence and Immersive Environments

2 Virtual worlds are considered immersive environments, and as such, it’s not unexpected that the element of social presence plays a rather important role. Virtual worlds have an advantage over traditional forms of distance learning in this area, since the avatar is represented by many of the familiar visual and social cues humans are used to. In Aragon (2003), social presence is defined as the “degree of salience of the other person in the interaction and the consequent salience of the interpersonal relationships” (p. 59). Immediacy, or the “measure of psychological distance that a communicator puts between himself or herself and the object of his/her communication,” can be conveyed by physical proximity formality of dress, physical proximity, facial expressions, and other nonverbal cues, as well as verbal (p. 59). This can apply directly to virtual worlds, since players are given control of all these social conveyances, and it is important because it lends to the immersion of the game.

Virtual worlds are considered immersive environments, and as such, it’s not unexpected that the element of social presence plays a rather important role. Virtual worlds have an advantage over traditional forms of distance learning in this area, since the avatar is represented by many of the familiar visual and social cues humans are used to. In Aragon (2003), social presence is defined as the “degree of salience of the other person in the interaction and the consequent salience of the interpersonal relationships” (p. 59). Immediacy, or the “measure of psychological distance that a communicator puts between himself or herself and the object of his/her communication,” can be conveyed by physical proximity formality of dress, physical proximity, facial expressions, and other nonverbal cues, as well as verbal (p. 59). This can apply directly to virtual worlds, since players are given control of all these social conveyances, and it is important because it lends to the immersion of the game.

What’s interesting, however, is that some research suggests the human interface control is not as relevant as one might think. A study in Aymerich-Franch (2010) revealed that participants who played a game by using their whole body did not experience any significant difference in presence or emotions than participants who played with a joystick. This implies that body-dependent systems such as the Wii and Kinect may not necessarily be more “immersive” to players, if we define immersion as a combination of social presence and emotions, and that we should look to other attributes when determining what makes one game more immersive than another. I would suggest that we should look more at the content of the virtual environment itself, than the human interface used to connect to it.

In another article by Lin (2010), an exploration of gender differences on game enjoyment is examined, as well as personal identification with the character. I feel this article misses the point, particularly when it claims that players are more likely to enjoy a game when the character they are playing is “morally justified” in the story or plot. In other words, a hero fighting for some sort of moral good. This seems logical, until one realizes that some of the top selling games like Grand Theft Auto don’t fit this mold, though one could argue that much of the villainous violence in these games follow a storyline causing the player to sympathize with the character. The genius of games like World of Warcraft is that both sides have sympathetic characters and heroes, and reasons for engaging the rival. The article sidesteps this issue by admitting that yes, some players are the opposite — even a significant number — and attempts to explain why. It seems self-contradictory.

I’ve been sporadically on Second Life since 2005, though only started taking it seriously since 2010, taking time to identify important locations, learn some scripting, and so on. I figured this was all worthy of a “rebirth” so I ditched my old character and created a new one. I think Second Life profiles are an important, yet perhaps underused element of social presence in a virtual world. They can serve to tie the avatar to a real user behind the screen.

People are a lot more prone to do things in Second Life they wouldn’t normally do in person. This is really nothing new, and applies to virtually all communication on the Internet. I think there is a degree of accountability that comes into play and prevents some severely offensive behavior when avatars are specifically identified with real people, but when there is full anonymity, it is rather chaotic and anarchic.

References

Aragon, S. R. (2003). Creating social presence in online environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(100), 57-68.

Aymerich-Franch, L. (2010). Presence and emotions in playing a group game in a virtual environment: The influence of body participation. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(6), 649-654.

Lin, S. (2010). Gender differences and the effect of contextual features on game enjoyment and responses. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(5), 533-537.

Sculpties and Meshes in Second Life and OpenSim

2Imagine a drafting class. Students are designing buildings in AutoCAD, laying out blueprints, and modeling the architectures. The teacher then tells everyone, “Okay, now add your buildings to the virtual city.” The students save their files, load up a program, and import the models into a virtual world. Within a few minutes, the world changes from a blank landscape to a rudimentary, populated town. The teachers and students can now walk around the town, examine the buildings, note areas needing improvement (“this wall’s bigger than the other” or “the ceiling here is lacking structural support”), and participate in a collaborative environment where teachers give prompt feedback to the group, and students can share their work with their peers.

It’s just one of many practical uses of virtual worlds in an educational setting, which goes beyond simply exploring the environment, to actually constructing content that can be assessed and evaluated. However, being able to import models constructed in third party utilities requires some additional work.

In Second Life and OpenSim, content is made using primitives: basic building blocks consisting of boxes, cylinders, cubes, pyramids, etc. that can be twisted, stretched, and otherwise manipulated, then linked to other primitives to create sophisticated objects. The method has a fairly low learning curve, but is limiting in how detailed models can be.

The texture map for the "sculptie"

An example of a "sculptie" image

Second Life and OpenSim also support “sculpties.” Sculpties are 3d models derived from colored graphic maps. In OpenSim, you can import terrain files composed of grayscale images. White indicates the highest elevations, while black indicates the lowest elevations. Sculptie maps are kind of like that, except with the additional colors more detail can be passed into the program to represent complex 3d models.

I’ve had mixed results with sculptie creation, particularly in OpenSim. At best, the tools for easily creating them are overly simplistic and don’t contain the features many students would probably require. At worst, the setup for sculptie support is more complicated than it should be. It’s certainly doable, but we have to keep in mind the less technical teachers and students when integrating this technology into the classroom, and the last thing we want is a teacher spending an inordinate amount of time trying to cross the bridge between the 3d modeling software and the virtual world.

The same model in OpenSim

A model made in Plopp SL

One tool I found intriguing is Plopp SL, a very easy-to-use program for simple 3d modeling and sculptie creation, aimed at young kids. Most modeling programs use a simulated three-dimensional space for sculpting objects, but Plopp SL allows users to just draw their objects the traditional pencil way, and the program then “inflates” the object like a balloon so it takes on a three-dimensional quality.

After that, you can export the sculptie map and the texture map, and load them up in OpenSim with the Imprudence Viewer (soon to be the Kokua Viewer). However, when I tried this, I ran into some problems when I tried importing the model. Shown here is an example of a doll I made in Plopp SL, which created the above sculptie textures, and how it looks in OpenSim itself. As you can see, it doesn’t quite render correctly in OpenSim. Maybe there’s some configuration setting that needs to be tweaked, but needless to say, I’m not entirely thrilled with sculpties after these experiments.

However, Second Life and OpenSim have now added basic support for meshes. A mesh is a collection of different shapes that make up a whole object. In most 3d modeling applications these are developed using wireframe models. Both virtual world applications still have a ways to go, but progress is being rapidly made.

So why do we want meshes instead of sculpties? Manipulating and linking primitives together has allowed the creation of some amazing work in Second Life/OpenSim, but there’s tremendous value to being able to create models using standard industry tools. Meshes allow direct compatibility with third-party 3d modeling programs our students use like Maya, Sketchup, and AutoCAD. All a student has to do is save their model in Maya (in the COLLADA format), and upload it directly through the Second Life viewer.

Other open source virtual world applications such as realXtend, a fork of OpenSim, and Open Wonderland have had mesh support for a long time. But Second Life Viewer 2 is the first Second Life viewer to support the mesh environment. OpenSim is not fully compatible with it yet, but it’s getting there. The Kokua project is building a new viewer based on Second Life Viewer 2. It has a sleeker interface than the old viewer upon which others like Imprudence, Hippo, and Phoenix are based. support. Kokua is the successor to Imprudence, and will be incorporating many new features, while remaining fully compatible with OpenSim and Second Life.

I believe there will be value to allowing our students to access Second Life in the future, so having a viewer compatible with both Second Life and OpenSim will be important. This may involve modifying the viewer with a whitelist of acceptable regions, or putting some other filtering utilities in place, but gaining access to the learning opportunities in Second Life will become an invaluable asset in our students’ future learning. This is one thing which prevents me from adopting realXtend. Which it is immensely cool, feature-rich, and visually appealing, it is heading in a different direction than OpenSim. It has its own viewer which is not compatible with Second Life, although the ModRex project aims to allow realXtend-OpenSim compatibility. It is still new, and whether that will translate to Second Life remains to be seen.

A demo of realXtend’s mesh and animation capabilities. Looks quite a bit better than Second Life/OpenSim, doesn’t it?

Virtual Worlds and Game-Based Learning Activities

2This past week I was wrapping up a draft of a synthesis paper about constructivist learning theory and its application to educational simulations and virtual worlds. I imagine there’s nothing new about wide-eyed educational technology students wanting an excuse to study games in school. It’s a pretty hot topic in education right now. As for me, I had a rather passive interest until our district’s IT Director approached me last year and asked some questions about how to start using virtual worlds in our district. I didn’t have an immediate answer for him. This became part of the reason I decided to enroll in Boise State’s M.ET. program.

I’ve already determined that using Second Life in our school district won’t be possible at this time, due to the adult content. There doesn’t seem to be any way for our district’s firewall to filter specific regions. We could actually customize our own Second Life viewer to whitelist a selection of regions that we’ve pre-approved, but this still won’t stop clever students from realizing they can download the standard viewer and access the inappropriate regions anyway. Teen Second Life also won’t work, since it’s intended for adolescents from 13-17 years of age, and apparently it’s rather difficult to even get Linden Lab to allow teachers on the site. Plus, none of these sites allow access for students 12 and younger, and the district never directly has any control over the actual content. The requirement for direct control is a policy we won’t be able to get around at the current time.

For this reason, the best alternative is to host our own virtual world server. OpenSim, an open source re-engineering of Second Life, appears to be a good bet. Version 0.7 was just released a few days ago with some pretty exciting updates. The drawback to a self-hosted virtual world, however, is that our students won’t have access to the vast array of pre-built regions in Second Life that contain undeniable educational value. What this means is that we’ll need to approach our use of OpenSim from another perspective.

For this reason, the best alternative is to host our own virtual world server. OpenSim, an open source re-engineering of Second Life, appears to be a good bet. Version 0.7 was just released a few days ago with some pretty exciting updates. The drawback to a self-hosted virtual world, however, is that our students won’t have access to the vast array of pre-built regions in Second Life that contain undeniable educational value. What this means is that we’ll need to approach our use of OpenSim from another perspective.

This is where learning theories come into play. We don’t have to wildly speculate what the best practices for using a multi-user virtual environment might be. We can draw from a deep pool of theoretical frameworks to make informed, educated decisions about how to create the most effective, engaging, motivating learning opportunities. Our young students do seem to be particularly fond of online gaming in general. Massive multiplayer online games (MMOGs) have increasingly become the dominant form of entertainment for children and adolescents (Paraskeva, Mysirlaki, & Papagianni, 2010).

It seems natural that a self-hosted virtual environment which has in-game modeling and scripting tools would naturally be an ideal playground for allowing students to become creators. Constructivist learning theories are a good fit, as they place the focus on learners, and cast them in active roles responsible for their own knowledge construction. Students can generate shareable artifacts in the virtual world. The teacher supports students’ learning, rather than dictates the information to them, and in the case of a virtual world, this would be accomplished by setting up virtual learning environments in which students can discover aspects the teacher wishes them to learn, and probably a few things they don’t expect, and allocating different tasks to students as they explore, test their theories to solve the tasks, and reflect on their learning.

In the game Spore by Electronic Arts/Maxis, for example, players guide the evolution of a species from a single-celled organism to fully sentient, intelligent, communicative beings that colonize the galaxy. Unlike scientific evolution, in which species are primarily the products of adaptive change, players have control over the appearance and many of the evolutionary characteristics of their creatures. Teachers could have their students form hypotheses about advantageous creature traits, and test them in the game world by building the creature accordingly through a simulated, albeit simplified evolutionary process. Through the process of discovery, students can learn:

In the game Spore by Electronic Arts/Maxis, for example, players guide the evolution of a species from a single-celled organism to fully sentient, intelligent, communicative beings that colonize the galaxy. Unlike scientific evolution, in which species are primarily the products of adaptive change, players have control over the appearance and many of the evolutionary characteristics of their creatures. Teachers could have their students form hypotheses about advantageous creature traits, and test them in the game world by building the creature accordingly through a simulated, albeit simplified evolutionary process. Through the process of discovery, students can learn:

- Basic principles of evolution as they advance through the different stages of the game

- Microbiology as they explore the primordial sea as a microorganism propelled by its flagella

- Zoology when they have to choose through their actions whether their creature is an herbivore, carnivore, or omnivore (this affects the primary cultural characteristics of the species later in the game)

- Astronomy as they explore other solar systems

- Politics when they encounter rival civilizations and are forced to coexist.

When things don’t go as planned, the students reform their hypotheses and test again. Part of this constructivist-based problem-solving model includes periods of reflection. It’s important that students, since they are their own knowledge constructors, have a chance to adequately reflect on what they are learning, and make the proper connections.

It’s almost inevitable that games not designed specifically for curricular learning will introduce inaccuracies, since there’s often a trade-off between entertainment value and realism. However, these points of inaccuracy can be teaching moments as well. For instance, asking “How is the evolution portrayed in Spore different from scientific evolution?” could prompt a great discussion in class. Spore is a rather fun tool for hypothesizing and fantasizing about how intelligent space-faring species might evolve, since as of now, humans are the only point of reference. But ultimately this demonstrates the advantage a fully-controllable virtual world provides, where you can design the simulation from the ground up so it follows particular curriculum standards and objectives, rather than having to mold a preexisting game around the curriculum.

I’m already considering the changes I’ll make to my paper for the final draft. It’s been nice to be able to draw on my past video game experience (and my parents thought I was just wasting time by playing them!) and adjust my perspectives with a new outlook.

References

Paraskeva, F., Mysirlaki, S., & Papagianni, A. (2010). Multiplayer online games as educational tools: Facing new challenges in learning. Computers & Education, 54(2), 498-505.

Review of "Learning Online with Games, Simulations, and Virtual Worlds"

1 Learning Online with Games, Simulations, and Virtual Worlds: Strategies for Online Instruction is a book by Clark Aldrich, an educational game consultant, which explains the benefits of different types of games, and contains suggested models for instruction. It is intended mainly for teachers and curriculum designers, but could also function as a good introduction to educational games for any interested layperson. It focuses on the preparatory work required to successfully implement educational games in a learning environment, and how to maximize their benefits for students and teachers. The book does more than just describe educational games and argue for their usage. It shows the reader how to identify opportunities for building games, use best practices, and outlines specific steps for developing, preparing, and designing game-oriented instruction.

Learning Online with Games, Simulations, and Virtual Worlds: Strategies for Online Instruction is a book by Clark Aldrich, an educational game consultant, which explains the benefits of different types of games, and contains suggested models for instruction. It is intended mainly for teachers and curriculum designers, but could also function as a good introduction to educational games for any interested layperson. It focuses on the preparatory work required to successfully implement educational games in a learning environment, and how to maximize their benefits for students and teachers. The book does more than just describe educational games and argue for their usage. It shows the reader how to identify opportunities for building games, use best practices, and outlines specific steps for developing, preparing, and designing game-oriented instruction.

There are three parts to this book. Part 1 argues for the use of games in education, and posits that virtual environments are actually a natural part of human thinking. Research and studies are referenced, demonstrating the effectiveness of games in education, and showing quite clearly how and why they work.

Different types of interactive learning activities are defined, and divided into three primary categories: games, simulations, and virtual worlds. Games are simpler activities that are meant to be engaging and encourage awareness, while simulations focus more on skill-building. Educational simulations are “structured environments, abstracted from some specific real-life activity, with stated levels and goals” (p. 7). Virtual worlds are “3-D environments where participants from different locations can meet with each other at the same time” (p. 8). Virtual worlds are noted for their detailed interactive models and real-time collaborative learning environment. Visual cues can play a part in virtual world learning, whereas they may not in the other types of interactive learning activities. These different types of activities are not mutually exclusive; there may be overlap among their components. Different types of simulations are broken down into several genres, and the author does a great job classifying the different aspects of games and levels of interaction.

The real meat of the book is in Part 2, which describes how to put highly interactive content into practice. These interactive learning activities are referred to as “Highly Interactive Virtual Environments” (HIVEs). The book mentions stumbling blocks that may be encountered from both students and teachers, and how to overcome them. Detailed steps are provided on how to use HIVEs, including preparing instructional material, obtaining technical support, how to build them or recruit others (such as students) to build the content, and how to determine the best courses of action. The book has a heavy focus on Second Life, and most of the discussion of virtual worlds directly references how to plan and accomplish tasks in Second Life. A lot of the tasks described are often best suited for a higher education environment, so someone in the K-12 field will naturally have to read through the filter of their own unique student safety and appropriate use policies.

A hypothetical setup and process for engaging students in a sim is described, with information about game interfaces, how to draw everyone in, setting the tone, determining learning objectives and outcomes, how to determine appropriate coaching during use, and the value of including competition as a game element to trigger motivation. The author also discusses how to deal with disinterested and frustrated students, and emphasizes the importance of tying the sim to real life.

Of course, knowing all this information about HIVEs is meaningless if you can’t convince your stakeholders that they’re worthwhile. Part 3 contains some much-appreciated and much-needed tactics for convincing administrators, parents, and politicians of the value of HIVEs. The author points out that advocating HIVEs requires that we don’t defend them blindly, but evolve them intelligently. Many people have the misconception that games “dumb down” learning material, simplifying it to a point that entertainment comes before usefulness. We must be able to demonstrate exactly how and why simulations can enrich, rather than flatten content.

The author also spends a good deal of time discussing methods for evaluating instruction in the simulations. In fact, an entire chapter is dedicated to this topic, with references to it throughout the entire book. The psychomotor skills that are often learned through sims can’t be measured through a multiple choice post-test. This is where formative evaluation comes in handy.

The book is shorter than one might expect, but it’s packed with information, and written concisely and informatively. The author gets right to the point. The main concepts are not over-simplified, and there’s a lot of detail specifically about how to approach different types of learning in HIVEs. The author drove home a good point for me: The goal is not to just recreate the classroom in a virtual world environment, but to provide an extension of the classroom that uses the virtual world’s advantages.

After reading this, my thoughts on virtual worlds have changed. I used to think that virtual worlds were just a good way to increase student engagement. Students like games, so naturally many of them would become more involved in the learning process if games were used, right? Well, it’s a lot more than that. There are times when an educational game, simulation, or virtual world is THE best form of instruction. What this book attempts to do is equip the reader with enough tools to recognize WHEN a game, simulation, or virtual world is the best form of instruction, and I think it does a good job of this.

References

Aldrich, C. (2009). Learning online with games, simulations, and virtual worlds: Strategies for online instruction. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Considering Virtual Worlds

0 I don’t know why some teachers take exception to calling virtual worlds “games.” Every time I’ve referred to Second Life as a “game” on Twitter, I receive a flurry of replies insisting “Second Life is NOT a game” and “You really think Second Life is a game???” I think it’s just the cultural mindset that “games are bad” yet “entertaining learning activities are great” even though physically there doesn’t have to be any difference.

I don’t know why some teachers take exception to calling virtual worlds “games.” Every time I’ve referred to Second Life as a “game” on Twitter, I receive a flurry of replies insisting “Second Life is NOT a game” and “You really think Second Life is a game???” I think it’s just the cultural mindset that “games are bad” yet “entertaining learning activities are great” even though physically there doesn’t have to be any difference.

I’ve only done a cursory examination of virtual world tools out there, and I hope by the end of my graduate school career, I’ll be able to write a full technology proposal for implementing this. As far as I’m concerned, Second Life is no good for a K-12 district-wide deployment, and here’s why:

- You’re stuck with either the teen grid or the adult grid.

- On the teen grid, parents and teachers aren’t even allowed.

- On the adult grid, students can run into inappropriate content.

- The teacher and district doesn’t have direct control over what students can do.

- Students less than 13 years old aren’t even allowed to be on Second Life.

There are other commercial providers that allow you to create your own virtual worlds. Active Worlds is probably the best one, but their educational pricing is quite steep: http://www.activeworlds.com/edu/awedu_pricing.asp $650/yr for a classroom of 20, and $395/yr after that. Assuming there aren’t bulk rates, for our school district that would be an initial investment of about $1 million, and $600,000 yearly after that. It’s completely unreasonable for a K-12 school system.

I found two that seem the most promising:

Multiverse: This is a hosted (cloud) solution, and has a completely free educational license. There is also an additional license that may be able to integrate with registered students. It appears to require a quote from Multiverse, and I haven’t followed up on this yet so I’m not sure how much it cost.

Multiverse: This is a hosted (cloud) solution, and has a completely free educational license. There is also an additional license that may be able to integrate with registered students. It appears to require a quote from Multiverse, and I haven’t followed up on this yet so I’m not sure how much it cost.

Models can be imported from Google Sketchup and Blender, which are both free 3d modeling applications, which means that schools wouldn’t need to invest huge chunks of money to provide modeling tools to students, and students could download these at home.- OpenSim: This is basically THE open source Second Life. You can install OpenSim on your own servers, and have complete control over it, and you can even use the Second Life viewer to access it. It’s still in early development, but it’s already creating quite a buzz. What’s more, the SLOODLE plugin, which integrates Moodle with Second Life and lets users take quizzes in the virtual world and submit virtual objects as assignments, generally works with OpenSim (though a few bugs still need to be worked out).

Google Sketchup models can also be imported into OpenSim, through realXtend (which itself may be a viable virtual world engine). If trying to maintain your own OpenSim server is too much of a burden, there are companies like ReactionGrid that provide hosted OpenSim solutions.

I’m excited to explore the possibilities with virtual worlds, and watch how the products mature. Hopefully we can come up with a solution that works well for everyone in our district, creates focused learning activities, and protects student safety all at the same time.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4cbd54c7-9b6e-45f5-93c0-6c3026876562)