Posts tagged evaluation

An Evaluation of Moodle as an Online Classroom Management System

0I’ve finished an evaluation of how our district uses Moodle, and areas where we can improve. You can read the report below.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be releasing some follow-ups to this evaluation. Addendums, if you will. I was originally planning to supply personal assessments of each participating online course in the initial report, using a rubric for hybrid course design. After some thought I scratched this idea, because much of the rubric falls outside the scope of the district’s objectives for using Moodle, which were included in the report from the outset.

Instead, I will be delivering each a brief mini-report to teachers who participated in the survey (there were 17), with suggestions and recommendations stemming from a combination of the rubric and the survey assessments, tailored specifically to your courses and instruction.

There’s a few things I’ve learned, that I’ll have to remember for the next time we do an evaluation like this.

- Don’t underestimate your turn-out. I was expecting 100, maybe 200 survey participants tops. What I did not expect was receiving 800 survey submissions that I had to comb through and analyze. There were some duplicate data that had to be cleaned up as well, since a few of you got a little “click-happy” when submitting your surveys. I also had to run some queries on the survey database to figure out what some of the courses reported in the student survey actually were, since apparently students don’t always call their courses by the names we have in our system. Since this was a graduate school project, there was a clear deadline that I had to meet, and it was a little more than difficult to manage all that data in the amount of time I had. I should have anticipated that our Moodle-using teachers, being the awesome group they are, would actively encourage all their students to participate in this project. I will not make that mistake again.

- Keep qualitative and quantitative data in their rightful place. Although I provided graphs with ratings on each of the courses, I had to remind myself that these were not strict numerical rankings, as they were directly converted from Likert scaled questions. The degrees between “Strongly Disagree” and “Strongly Agree” are not necessarily the same in everyone’s mind, so when discussing results, one has to look at qualitative differences and speak in those terms. For example, if the collaboration “ratings” for two courses are 3.3 and 3.5 respectively, one can’t necessarily say that people “agreed more” with Course 2 than Course 1. There may be some tendencies that cause one to make that assumption, but one shouldn’t rely on the numerical data alone. To brazenly declare such a statement is hasty. If the difference had been significant, such as 1.5 vs. 4.5, then there would likely be some room for stronger comparisons.

- Always remember the objectives. When analyzing the data, it’s easy to get sidetracked with other interesting, but ultimately useful data. For example, a number of students and teachers complained about Moodle going down. This was a problem awhile ago, and it caused some major grief among people. However, it was not relevant to any of the objectives for the evaluation, even though it was tempting to explain/comment/defend this area. I take it personally when people criticize my servers! (Just kidding.)

- If the questions aren’t right, the whole evaluation will falter. Even though I had the objectives in mind when I designed the survey, I still found it difficult to know which were the right questions to ask. I’ve been assured that this aspect gets easier the more you do it. In the end, there was some extraneous “fluff” that I simply did not use or report on, because it wasn’t relevant (e.g. “Do the online activities provide fewer/more/the same opportunities to learn the subject matter?” My initial inclination was to include this in the Delivery, but when I finally looked at the finished responses, I realized it didn’t really fit anywhere and wasn’t relevant to any of the objectives.

Right now, being the lowly web manager that I am — and I only use the term “web manager” because “webmaster” is so 1990s; I don’t actually “manage” anyone — I don’t get many opportunities to do projects like this. But I’m aspiring to do more as a future educational technologist. Evaluations are more than just big formal projects … they underscore every aspect of what we as educators do. Teachers would do well to perform evaluations of their own instructional practices. When we add new programs or processes in our district, evaluations should accompany them. And as I complained in my mini-evaluation of BrainBlast 2010 a few days ago, all too often the survey data we gather just aren’t properly analyzed and used. We have some of the brightest minds in the state of Utah working in our Technical Services Department, but often we just perform “mental evaluations” and make judgments of the direction things should go, when we would do well to formalize the process, gather sufficient feedback, and use it to make informed decisions.

Update on the Moodle Survey

0 Last week I invited all our Moodle-using teachers and students to take a survey about their usage of Moodle as an online course management system and supplement to in-class instruction. The response has been great. So far (as of November 23, 9:30pm), 652 students and 17 teachers have participated. The survey was supposed to close today, but at the request of the teachers and students, I am leaving it open until November 30.

Last week I invited all our Moodle-using teachers and students to take a survey about their usage of Moodle as an online course management system and supplement to in-class instruction. The response has been great. So far (as of November 23, 9:30pm), 652 students and 17 teachers have participated. The survey was supposed to close today, but at the request of the teachers and students, I am leaving it open until November 30.

The survey questions assess four categories: (1) Participant Attitudes, (2) Collaboration, (3) Instructional Preparation, and (4) Instructional Delivery. There are a few goals I’m keeping in mind. One is to help determine the collaborative effect of our usage of Moodle. During the last BrainBlast, we taught a session to (almost) every secondary teacher in attendance: “Creating Collaborators with Moodle.” This begs the question, “Just how well are we currently using Moodle for collaboration?” Where can we improve? Our teachers have had the opportunity to put what they learned in the Moodle class into practice, so has the collaboration aspect improved? The survey addresses this.

Another goal is to address if Moodle actually reduces instructional preparation time. Our teachers have commonly criticized Moodle for being too time-consuming. This is a valid concern, and there are questions addressing the preparation time of the two major activities our teachers use in Moodle: assignments and quizzes. The delivery aspect of Moodle is important, too. Are students more engaged when they use Moodle? Is it easier for them to submit their homework? Does using Moodle save them time as well?

Originally, I was planning on correlating Moodle usage with academic performance, but after consulting with my professor, Dr. Ross Perkins, I realized that there are too many factors involved to even suggest some sort of link between the two. Moreover, the instruction itself is key, not necessarily the tool of delivery. What’s more, I think such a question starts crossing territory into more of a research project than an actual evaluation. It would be incredibly useful to research and establish best practices for online course delivery; the present scholarship in this area is huge and constantly evolving, but a lot of work remains to be done. However, it is outside the scope of this evaluation.

Most of the Moodle survey uses a Likert scale (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) for the questions. There’s considerable debate over whether scales like this should employ a middle ground (e.g. Neither Agree nor Disagree) by providing an odd number of answers, or force participants to choose a position by providing an even number of answers. After tossing the two options back and forth in my mind, I decided on providing a middle option for the questions. I’m wondering now if that was a mistake. I believe it introduces a degree of apathy into the survey that, in hindsight, I didn’t really want. A lot of the participants are choosing “Neither Agree nor Disagree” for some of their answers, when I suspect they probably mean “Disagree.”

Ultimately, though, the data are still valuable. Apparently, most students do not feel that they are given many opportunities to collaborate in Moodle. Teachers generally agree that they don’t bother to provide these opportunities for collaboration. Perhaps as a follow-up, I should ask the teachers why they don’t provide collaborative opportunities, especially those teachers who attended the BrainBlast session.

The data also indicate that both students and teachers generally agree that Moodle saves time in both preparation and instruction. The disagreements here come mainly from math teachers who complain about Moodle’s general lack of support for math questions (DragMath is integrated into our Moodle system, but this isn’t enough), and the inability to provide equations and mathematical formulas in quiz answers. This is undoubtedly worth further investigation. I came across a book on Amazon (Wild, 2009) that may provide some valuable insights.

The data also indicate that both students and teachers generally agree that Moodle saves time in both preparation and instruction. The disagreements here come mainly from math teachers who complain about Moodle’s general lack of support for math questions (DragMath is integrated into our Moodle system, but this isn’t enough), and the inability to provide equations and mathematical formulas in quiz answers. This is undoubtedly worth further investigation. I came across a book on Amazon (Wild, 2009) that may provide some valuable insights.

The participants are prompted to provide open-ended comments as well. Answers fell all across the spectrum, from highly positive (e.g. “I love taking online courses; it’s easy, organized, and efficient…”) to extremely negative (e.g. “I hate everything about it; online schooling is the worst idea for school…”). The diverse answers will be addressed in the final report.

The survey isn’t the only measurement tool I’m using. I’m also going to employ a rubric to assess each online course represented in the survey. There are few enough (in this case, about 20) that this is a reasonable amount to assess within the given time. After that, I just have to write up the final report, create some graphs of the data, analyze the results, and provide recommendations.

References

Wild, I. (2009). Moodle 1.9 Math. Packt Publishing.

BrainBlast 2010 Survey Results

2 In the first week of August 2010 we wrapped up our 4th annual BrainBlast conference. It was quite a success. After 4 years, things tend to run a lot smoother at BrainBlast than they used to. According to most of the participants, the training was great, the keynote speakers were outstanding, and the food from Sandy’s was excellent. We did a few things differently this year. One big change is that we’re making a considerable push toward Moodle in our district, having already made it available to our teachers as an online classroom management system for the past 3 years. For BrainBlast 2010, we made sure almost every secondary teacher was enrolled in a Moodle session by providing enough sessions teaching this great tool. We’re also upgrading to Windows 7 in our district this year, and provided Windows 7 training to teachers in the first phase of the transition.

In the first week of August 2010 we wrapped up our 4th annual BrainBlast conference. It was quite a success. After 4 years, things tend to run a lot smoother at BrainBlast than they used to. According to most of the participants, the training was great, the keynote speakers were outstanding, and the food from Sandy’s was excellent. We did a few things differently this year. One big change is that we’re making a considerable push toward Moodle in our district, having already made it available to our teachers as an online classroom management system for the past 3 years. For BrainBlast 2010, we made sure almost every secondary teacher was enrolled in a Moodle session by providing enough sessions teaching this great tool. We’re also upgrading to Windows 7 in our district this year, and provided Windows 7 training to teachers in the first phase of the transition.

General Statistics

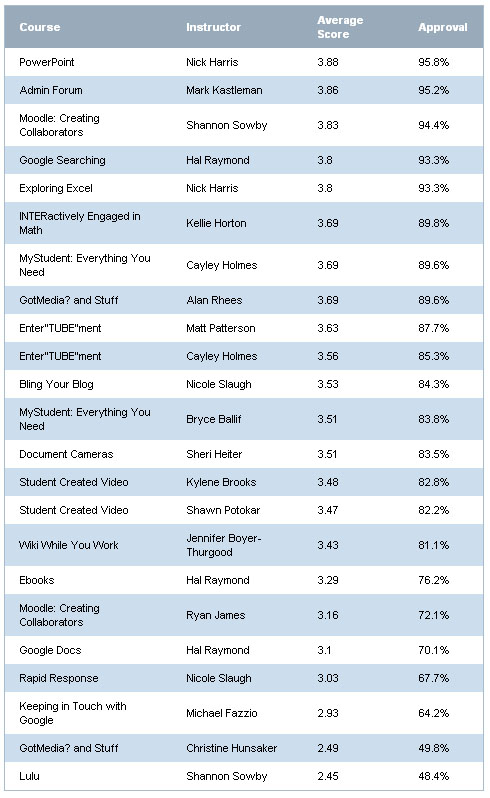

218 people participated in the survey. This number comprises 63% of the attendees, specifically 210 (70%) of the teachers, and 8 (18%) of the administrators. Table 1 indicates the highest-ranking courses, with the average scores for each on a scale of 1 to 4.

Table 1: Course Rankings and Approval

Mark Kastleman was a huge hit both in his first-day keynote session and the two follow-up sessions he held with the administrators. Barely outranked only by Nick Harris’ PowerPoint session, he delivered quite a dynamic keynote presentation about the relationship between the brain and learning. We were fortunate and appreciative that he and Mike King were able to share their insights at BrainBlast, and that Mark was able to provide follow-up sessions for the administrators.

This year we made sure to collect data on what people didn’t like about the conference. That was a major focus of the survey results, and we intentionally gathered negative feedback, which constituted most of the comments returned. We want to know what we’re not doing right. Constructive criticism will be one of the most helpful things to guide future BrainBlasts. The following information is not intended to be a “slam” against BrainBlast or anyone involved in organizing this excellent training event. Instead, I hope the comments prove helpful in optimizing and enhancing the learning experience for all BrainBlast participants. Some of the most common themes that popped up in the survey results are highlighted below.

Irrelevancy of the Classes

“I would have liked to actually been in the classes that I registered for. There were only two classes on my schedule that I wanted to be in. The others I did not register for, which was kind of annoying.”

“The hardest thing is when you are signed up for classes that you are not interested in at all. I have no desire to do Moodle and I was enrolled in the class for a second year in a row. Last year was fine, but this year I had no desire to listen. Is there a way we could let you know what classes we don’t want to take along with the ones we do?”

“Design [the] number of classes to accommodate number of students asking for them so you get the choices you want.”

“I felt that I was already pretty versed in [MyStudent] and didn’t learn anything new. I was not happy with having to take it over courses like Blogs!”

Many participants commented that they already knew the material in the classes they were selected for, or that they didn’t get any of the classes they wanted and that the material wasn’t relevant to them at all. This was an especially common concern in the Lulu class, as well as a few others. “It was not made clear how we would use the websites offered in [the Lulu] course,” one participant noted. “The online books seem too expensive to use in the classroom.” Another stated that Lulu “did not really apply to my curriculum.” “I didn’t really see the practical application of how I could use [Lulu] in class,” agreed yet another teacher. The common concern was that Lulu books tend to be too expensive for most parents.

A couple factors are directly related to the participants having been placed into classes not relevant to them:

- We did not collect much information at registration about teachers’ existing skill sets, let alone use this information to place teachers in classes that would be suitable for them.

- We did not use the wishlisted courses to determine how many sessions to offer. Last year, the average participant got 68% of the courses they wishlisted. This year, the participants only got 16%. The reason is this: When participants initially registered, they specified up to 6 courses they would like to take. They did this last year, too, except this year we did not delineate these courses by their track (elementary, secondary, or administrator). As a result, a lot of participants were wishlisting courses in tracks that would not be available to them. Elementary teachers were wishlisting courses in the secondary track, secondary teachers were wishlisting courses in the elementary track, and all teachers were wishlisting courses in the administrator track.

The bottom line is, we may as well have not even bothered with a wishlist, since it hardly determined which classes were assigned to whom.

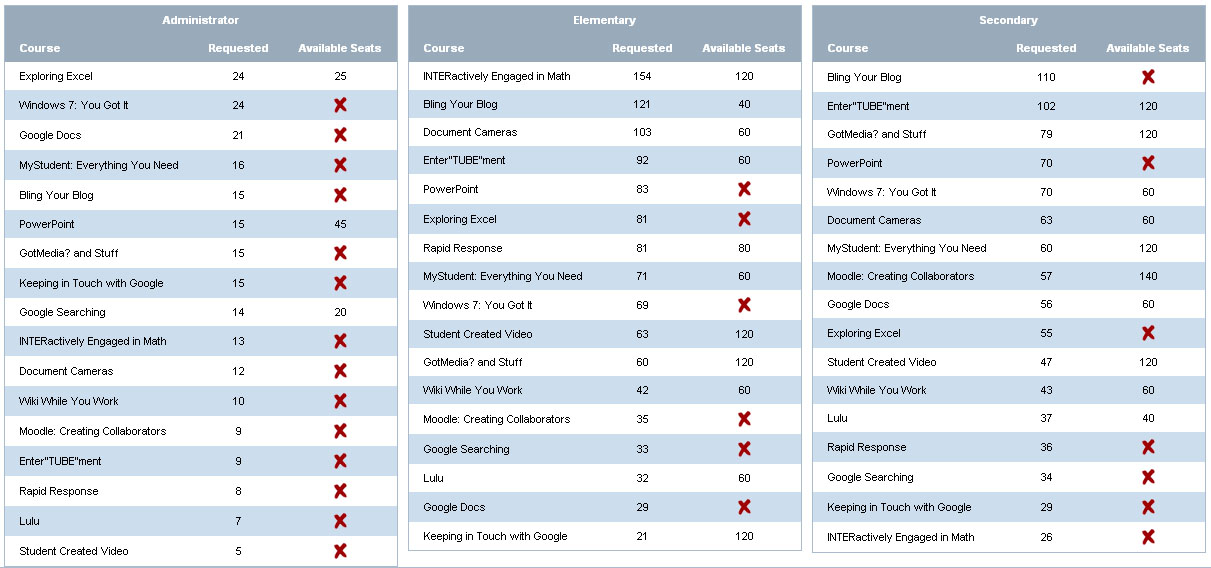

Table 2 indicates the preferred courses per track, as well as whether or not the course was even available in the track. The second column in each table shows the number of times the course was wishlisted during the initial registration, and the third column shows how many slots we actually provided for the course for the entire conference.

Table 2: Preferred Courses vs. Available Seats (click to enlarge)

Bling Your Blog! was one of the most requested classes (246 participants requested it), yet we only made room for 2 sessions (40 participants, or 16% of the requesters), and only in the elementary track. “I would have liked to attend a course on blogs,” remarked one teacher. “That was the one I wanted the most, but didn’t get to go to it.” “Please have a course on creating blogs for beginners,” begged another, “and have enough sessions [so] all who want it can have it.” Conversely, Lulu was one of the most unrequested classes. Only 76 requested it, yet we provided room for 5 sessions (100 participants). And we provided 6 sessions (120 participants) of Keeping in Touch with Google for elementary teachers, yet only 21 in the elementary track actually requested it! It’s hardly a surprise that these two ended up as some of the lowest ranking courses in the survey results, with so many disinterested people forced into them.

Recommendations for Improvement

Even if it means we need to open up BrainBlast registration earlier to allow for more planning time, we should consider the wishlisted classes and provide a suitable number of sessions to accommodate them. However, there is still value to a strictly randomized scheduling process. Teachers may attend classes they would not have normally requested due to an unfamiliarity with the material, but once they participate in the class they acquire new knowledge and skills directly relevant to their subject, classroom, and instructional strategies. At least, that’s one factor that has driven the design and development of BrainBlast. Every class should be relevant to everyone. Clearly, we did not accomplish that this year.

We should not discount the role a teacher’s general disinterest plays. If they simply don’t care about the subject material when they walk into the class, this preconception will carry all the way through, and stifle any engagement and learning they may experience. We need to find a way to identify which courses may be most relevant to a teacher, even if they don’t know it themselves. At the very least, a middle ground should be found between encouraging teachers to explore new technologies, and supplying the correct number of classes they specifically choose and feel are most relevant to them. As one teacher helpfully recommended, “Make sure that the courses are relevant to the participant . . . the majority of the courses were not very applicable to me. Plus, I only received 1 out of 6 courses that I had selected. The ones I had chosen would have been extremely relevant!”

Separation of Beginner and Advanced Classes

“It is frustrating to be in a course and want to learn more than you already know and it is based around the beginner.”

“Within the first part of the class I had things figured out, but we couldn’t move into more depth because there were other people in there that struggled.”

“Please, please, please have a beginners track and an advanced track. It is SO frustrating to not be able to learn anything new because the instructor runs out of time due to the fact there are people in the class that can’t even open the program they are talking about. ‘Wait! Slow down! How did you open Windows Movie Maker?!’ Very frustrating!”

“Some of the presenters tried to teach too much and I was way behind and couldn’t keep up.”

“Make a track that separates those who have little / no experience and those who have more experience and want to go deeper.”

The suggestion to divide classes by skill sets was very common this year. “Organize the classes by beginner, intermediate, advanced as well as by subject,” a teacher recommended. “It gets very frustrating to be in a class where the teacher is trying to explain a more complex subject and some of the students can’t even remember how to login or what the Internet icon looks like.” “I really feel that classes need to start being identified as beginner classes and classes for more advanced learners,” commented another. “A couple of the classes attended were not as helpful because they are skills I have learned at previous BrainBlasts.”

The suggestion to divide classes by skill sets was very common this year. “Organize the classes by beginner, intermediate, advanced as well as by subject,” a teacher recommended. “It gets very frustrating to be in a class where the teacher is trying to explain a more complex subject and some of the students can’t even remember how to login or what the Internet icon looks like.” “I really feel that classes need to start being identified as beginner classes and classes for more advanced learners,” commented another. “A couple of the classes attended were not as helpful because they are skills I have learned at previous BrainBlasts.”

This is not a bad suggestion, and there’s no denying that teachers attending BrainBlast have a wide range of abilities. Some come to the conference as technology experts, others as beginners, and this creates problems and negative feelings from different people in the classroom. “Have the instructors not wait for the one or two that don’t get it or are behind to catch up with the class,” recommended one teacher. “It really wastes time for those (the bulk of the class) that are ready to move to the next step.” The in-room techs should be able to help teachers catch up so the teacher doesn’t have to stop and wait, and perhaps we need to make that role more clear to them. However, it is rather difficult to create classes that appeal to everyone, when a few people are holding things back. It also creates a poor learning experience if some participants are constantly behind and relying on the school techs to assist them, just to keep up with the teacher.

Recommendations for Improvement

There is a need to organize classes into beginner and advanced, even if these are subdivisions within the elementary and secondary tracks. Our teachers have widely varied skill sets, and if we’re going to be randomly assigning them to classes, we shouldn’t operate under the assumption that “one class fits all.” Evaluating different technical skills is tricky, but well-crafted skill assessments should occur at registration time. At the very least, the random assignments should occur within subsets of designated beginner and advanced classes.

No More Shirts!

“Please get rid of the shirts and use that money for prizes.”

“If you must keep the shirt, make it a t-shirt. They’re cheaper.”

“Use the money spent on shirts to go towards equipment to be used in the classroom.”

“Give us more useful tech stuff. I would rather have had a tripod than a shirt.”

“No more shirts, they are atrocious and they are a waste of money.”

The general disdain for shirts was yet another common manifestation. I believe there is value to making BrainBlast shirts available to all who want it, but perhaps for next year participants could opt out of receiving a shirt when they register.

Other Ideas: Workshops

“I would like to have the option of being able to take the full two days to have a working workshop in Moodle,” suggested one teacher, “so that I can come away with tangible material that I can use in the classroom.” Day-long workshops are not uncommon to technology conferences, and some will provide this option, typically on an optional last day. Other times this is done during the regular conference schedule, so the participant enrolls in day-long workshops in lieu of a diversity of classes. Generally, the idea for BrainBlast has been to provide a good range of classes to expose teachers to multiple technologies, and to set aside workshop-oriented instruction for E-volve and iLead classes. However, many participants mentioned that the class time was too short to reasonably cover the material:

“I would like to have the option of being able to take the full two days to have a working workshop in Moodle,” suggested one teacher, “so that I can come away with tangible material that I can use in the classroom.” Day-long workshops are not uncommon to technology conferences, and some will provide this option, typically on an optional last day. Other times this is done during the regular conference schedule, so the participant enrolls in day-long workshops in lieu of a diversity of classes. Generally, the idea for BrainBlast has been to provide a good range of classes to expose teachers to multiple technologies, and to set aside workshop-oriented instruction for E-volve and iLead classes. However, many participants mentioned that the class time was too short to reasonably cover the material:

“Most of the classes went by too fast, especially on wikis. I had never even heard of one and there was just not enough time to really understand.”

“Make more ‘beginning level’ classes available and expand time on some of the sessions so we have more time to ‘create’ or to produce a finished product.”

“Some classes need to spend more time on basics. Go deep instead of broad.”

“Got Media & Stuff was the weakest because it contained so much info and not enough time to explain about each site.”

“Student Created Video would have been better if there was enough time. The time was cut short due to the general session going over a bit.”

“Could have used more time in Bling My Blog….and Google…”

Whether or not longer, focused workshops would incorporate well into BrainBlast remains to be determined. With our training efforts, it would probably be more suitable to divide workshop-based courses into other training venues, such as E-volve or iLead.

Other Ideas: Virtual BrainBlast

“It would be nice to have this more than once a year,” suggested another teacher. I’m reminded of FETC, which is one of the largest annual educational technology conferences in the U.S. Most educators are probably familiar with it, but many do not know that they also host Virtual FETC conferences a couple times throughout the year. The online version of FETC is portrayed in a virtual web-based environment with INXPO’s Virtual Events & Conferences. Participants can travel around the virtual conference setting, viewing products and communicating with vendors in real-time, collecting virtual memorabilia, taking notes, and interacting with other educators online. Sessions are broadcast at set times, typically chosen from archived recordings of the last FETC, though live streams are possible, too. During the sessions, participants can, and are even encouraged to chat amongst each other about the topic being presented. Some have claimed that the best learning during a conference happens before and after the sessions, when everyone networks together to talk about what was learned, explore how they can apply the new information, and share their own insights to a group of eager-to-listen professionals in their field. Collaboration is a hugely beneficial aspect of any conference, and virtual conferences are ideal for this form of collaboration. Many participants can gather together in the same room, more than would be possible in a physical setting, and have the opportunity to collaborate with the group in a way that might not be as easily accomplished at a large meeting of educators.

“It would be nice to have this more than once a year,” suggested another teacher. I’m reminded of FETC, which is one of the largest annual educational technology conferences in the U.S. Most educators are probably familiar with it, but many do not know that they also host Virtual FETC conferences a couple times throughout the year. The online version of FETC is portrayed in a virtual web-based environment with INXPO’s Virtual Events & Conferences. Participants can travel around the virtual conference setting, viewing products and communicating with vendors in real-time, collecting virtual memorabilia, taking notes, and interacting with other educators online. Sessions are broadcast at set times, typically chosen from archived recordings of the last FETC, though live streams are possible, too. During the sessions, participants can, and are even encouraged to chat amongst each other about the topic being presented. Some have claimed that the best learning during a conference happens before and after the sessions, when everyone networks together to talk about what was learned, explore how they can apply the new information, and share their own insights to a group of eager-to-listen professionals in their field. Collaboration is a hugely beneficial aspect of any conference, and virtual conferences are ideal for this form of collaboration. Many participants can gather together in the same room, more than would be possible in a physical setting, and have the opportunity to collaborate with the group in a way that might not be as easily accomplished at a large meeting of educators.

Virtual conferences are not unusual. Second Life is another popular platform for delivering virtual conferences such as Virtual Worlds: Best Practices in Education (WBPE), SLanguages, UNC: Teaching and Learning with Technology, SLACTIONS, and others. While I wouldn’t advocate opening up Second Life to all teachers inside the district (not at this point, at least), this could be a viable platform for a virtual BrainBlast. But on the other hand, a virtual BrainBlast wouldn’t need to be so sophisticated. Just gathering teachers in a basic web-based environment where they can communicate and participate in great training has tremendous benefits. And it would be a considerably more cost-effective supplement to BrainBlast than the summer event at Weber High School.

Evaluating Learning

One obvious question we may be overlooking is, “How well do we assess the learning of the participants?” BrainBlast is designed to be a highly constructionist, hands-on learning experience. Every classroom is equipped with a computer lab, and during the sessions the participants are expected to produce concrete artifacts and gain both conceptual and procedural knowledge of specific technology tools. Yet no official learning evaluation process is in place that I’m aware of. At the very least, the instructors and school techs stationed in each room should take notes during or after the training sessions of the overall learning experience, common problems that arose, and answer questions regarding the effectiveness of the session. The direct observation would prove invaluable in determining which instructional strategies do and do not work.

There are three particular aspects we should measure in any evaluation: efficiency, effectiveness, and impact. BrainBlast is undeniably efficient: all participants are given a wide range of training within a 12-hour timeframe over 2 days. The effectiveness is a little more debatable. Do all participants leave the sessions knowing the material they were supposed to learn? Are there always clear objectives in each class that should be accomplished by each participant? While we don’t want participants to take a grueling multiple choice quiz at the end of each session to determine if they actually learned anything, we can assess their learning by viewing their completed artifacts.

However, does BrainBlast actually have an impact? After a teacher takes a blogging class at BrainBlast, do they become an active blogger throughout the school year? If a teacher receives training on using Flip Video cameras, do they start using this in their class, and finding ways to engage students with video creation? 140 secondary teachers received training in Moodle. And now, a few months later, we still only have about 30-40 teachers actively using our Moodle system. This is about the same number of teachers that were using Moodle last year. Did BrainBlast actually have an impact on Moodle usage?

Granted, we shouldn’t expect teachers to use all the educational technology tools they have learned about in their daily instruction, but currently we do not formally measure if teachers are using what they learned a month, three months, or six months after the event. From past experience, and having received the most basic questions on how to blog, upload WeberTube videos, use a document camera, etc. from teachers that knowingly have participated in BrainBlast’s related training venues, the effectiveness and impact of BrainBlast needs to be determined.

Where is Social Bookmarking?

![]() I commented on this topic 2 years ago after BrainBlast 2008. Classes on social bookmarking have been strangely absent from BrainBlast’s course offerings. Since 2007, Delicious, the most popular social bookmarking tool, has been consistently ranked as the top #1 and #2 most useful tools for learning by the Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies, which gathers data and feedback from educators all over the world. Why is social bookmarking such an important tool for teachers? There are numerous educational resources on the web, and social bookmarking is the most popular and effective way for teachers to share them amongst each other. It’s not just ordinary things like math manipulatives or quiz sheets that are shared, but links to videos, podcasts, desktop applications, helpful teacher blogs, educational trends, and bleeding-edge teaching ideas. The worldwide teacher network is opened up through social bookmarks, and our teachers can tap into this learning network by taking their bookmarks online.

I commented on this topic 2 years ago after BrainBlast 2008. Classes on social bookmarking have been strangely absent from BrainBlast’s course offerings. Since 2007, Delicious, the most popular social bookmarking tool, has been consistently ranked as the top #1 and #2 most useful tools for learning by the Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies, which gathers data and feedback from educators all over the world. Why is social bookmarking such an important tool for teachers? There are numerous educational resources on the web, and social bookmarking is the most popular and effective way for teachers to share them amongst each other. It’s not just ordinary things like math manipulatives or quiz sheets that are shared, but links to videos, podcasts, desktop applications, helpful teacher blogs, educational trends, and bleeding-edge teaching ideas. The worldwide teacher network is opened up through social bookmarks, and our teachers can tap into this learning network by taking their bookmarks online.

Saving social bookmarks is as easy as installing the Delicious add-on in your browser and clicking Save. It’s no more complicated than clicking “Add to Favorites” in Internet Explorer. Plus, you can access your bookmarks from any computer, so you don’t have to panic when you realize that cool link to the video you wanted to show your class was bookmarked on your home computer, but not your work computer. Social bookmarking is such an invaluable asset. No longer do you have to hunt for your own resources for your classroom lessons, but you can tap into the research that thousands of other teachers have done and find existing links that others have shared. New links can be emailed to you daily, or you can subscribe to RSS feeds of bookmarks shared by different users, or bookmark groups that are created around topics. 99% of Weber School District’s Links of the Day come from Delicious and Diigo (another popular social bookmarking service which has some great extra features like highlighting and annotating pages). And about 99.9% of the links that get sent to my inbox are never put up on the Links of the Day page, so it would be beneficial if teachers have access to these other links themselves.

The bottom line is this: Our teachers are going to a technology conference, to learn about tools for learning and teaching. They are sitting in computer labs and learning about great web sites. But what do they do when they want to save these links? They whip out their notebooks and pens and write them down. These could easily be saved with a simple click and the teacher could access it later from any computer. The final step in the process is absent. All the BrainBlast links could even be merged into a shared bookmark group that anyone, anywhere can access for future reference. It’s rather strange that one of the top tools for learning has never even been mentioned at BrainBlast.

Conclusion

Overall, participants were quite happy with how the conference played out. There is clearly some room for improvement, particularly in ensuring the classes are relevant to everyone, and taking unique skillsets and aptitudes into account when the participants’ classes are assigned. We must improve our evaluation procedures as well, and pay careful attention to collecting good, reliable data if we are to determine how best to improve this event. There may be some value to including an online venue to supplement BrainBlast, and making sure that all the materials are easily accessible at a later date.

And finally, the best suggestion we received from the survey:

Analyzing the Problem

0 We solve problems every day. Sometimes the problems are simply figuring out where you left your car keys. Other times, it’s determining the best way to reach the unique needs of your students. Often we solve these problems without really thinking through the process. We just mentally “connect the dots” and arrive at conclusions. The conclusions may not necessarily be the best ones, or we may not always explore all the options at hand. In most cases, for mundane tasks, it’s not really necessary. When you can’t find your car keys in one location, you naturally move on to another until they’re located. But some situations may warrant a more in-depth analysis of the problem.

We solve problems every day. Sometimes the problems are simply figuring out where you left your car keys. Other times, it’s determining the best way to reach the unique needs of your students. Often we solve these problems without really thinking through the process. We just mentally “connect the dots” and arrive at conclusions. The conclusions may not necessarily be the best ones, or we may not always explore all the options at hand. In most cases, for mundane tasks, it’s not really necessary. When you can’t find your car keys in one location, you naturally move on to another until they’re located. But some situations may warrant a more in-depth analysis of the problem.

Analyzing a problem is the intermediary step between recognizing the problem and arriving at a solution, and it involves using data collection and forming decision-making strategies. Defining clear goals and objectives is important, too. For BrainBlast 2010 last summer, we had all the attendees participate in a survey on the final day of the conference. The goal was to collect data to enhance the quality of instruction for future conferences, and we collected some valuable information to this end, through a combination of Likert scale questions, and prompted constructive criticism. With these data, we can form the necessary decisions to improve future BrainBlasts, and avoid repeating any mistakes we made in the past.*

An evaluator must assess aspects such as the needs of the program and its users. It’s important to be aware of the different data-collection tools at one’s disposal as well. My own forthcoming Moodle evaluation will be largely interview-based, with some backend data collection assessing general academic performance averages and usage of online course activities. Interviews in particular are useful formative evaluation tools. It’s important to not neglect formative evaluation during a program, as it can reveal scenarios, ideas, and possible venues for improvement before the conclusion.

Objectivity is important as well when analyzing a problem. After all, if an evaluation isn’t objective and free of bias, it is worthless. While it’s likely not possible that an evaluator can completely cast their biases aside, especially when offering professional recommendations, it’s important they make every effort to do so. Also, detailing the steps the analysis took and the efforts to collect objective data goes a long way.

* An analysis of the BrainBlast 2010 survey results will be posted in a few days. (Update: survey results are now available.)

Analysis of Three Evaluation Reports

0The USOE 2005 Summative Evaluation Report reads more like a commentary than an evaluation, and is very poorly executed. Data analyses are not conveyed in any meaningful forms or visualizations. Numerous spelling and grammar errors persist. The report doesn’t seem to address any particular objectives or self-defined goals in each program, and is highly disorganized and difficult to follow.

The data analysis for Everyday Math contains excellent visuals. A valid point is raised that performance data in education is difficult to evaluate, since there is often not a control group. Both the parent and teacher surveys cover the most pertinent aspects involved in the program, and are in accordance with the National Mathematics Advisory Panel’s report in Appendix B. However, the recommendation to pilot alternatives to Everyday Math is not necessarily the next logical step based on the evidence. The evaluation consists primarily of attitude assessments, rather than performance assessments. There are multiple reasons why a program would fail, and Everyday Math’s problem might simply be due to improper training among the teachers, a factor which wasn’t considered in the report. The Executive Summary itself isn’t necessarily supported by the text, and at best refers to vague references to math scores consistently improving over time, and the lack of evidence that Everyday Math leads to better performance.

The Technology in Teacher Education—Nevada: Project TITE-N report contains a diverse selection of data which appears to adequately cover the pertinent topics relevant to pre-service teachers. Measurement tools are very well-documented, and referenced frequently throughout the text, particularly in the informative visual displays of the data. There is, however, the necessity to familiarize oneself with the abbreviations before reading the data analyses charts. Figure 10 contains colors that are too close to distinguish, and Figure 14 contains blank items in the legend. Overall, the evaluation was well-done, with dissimilar groups being surveyed to ensure breadth of applicability, and with conclusions that accurately match the data portrayed.

Plans for an Evaluation of Weber's Moodle System

0I’m conducting an evaluation of WSD Online, our district’s Moodle system. Right now, we use this as our online classroom management tool. We’re just barely piloting fully-online courses, but that’s not what I’m evaluating. Right now more than a few of our teachers use Moodle as a supplement to their in-class teaching. I’ve decided to evaluate four primary areas regarding our use of Moodle:

- How student engagement in our classes is impacted when Moodle is used

- If the most popular activities our teachers use in Moodle (in ascending order: quizzes, assignments, and forums) actually reduce teacher preparation time

- How the usage of Moodle activities impacts attitudes among teachers and students, such as quiz-building, assignments, over the traditional forms of delivery, and

- How Moodle affects the academic performance of students

I’m interested in hard data on how the groups perform compared to non-Moodle-using groups. We only have between 20 and 30 teachers actively using Moodle, which isn’t significant enough for gathering districtwide data. However, I can gauge the results on an individual course basis by comparing academic performance of the students in the teacher’s class with the usage of Moodle, to how the students performed before the teacher used Moodle to supplement the learning environment.

With the help of some of my classmates I’ve evaluated a few other web sites, or web-based learning environments to be exact. A rubric designed by Baya’a, Shehade, & Baya’a (2009) was used to assess usability, content, value, and vividness of each site, to produce a criterion-referenced evaluation report. It did help me understand some of the strengths of using a rubric to assess content, when there are identifiable criteria to evaluate. It also helped me recognize this is probably not the way I want to go for the WSD Online evaluation, since any criteria I assign will be fairly arbitrary at this point. The norm-referenced approach will probably be more useful, because I can directly compare our Moodle-using teachers and students to non-Moodlers.

References

Baya’a, N., Shehade, H. M., & Baya’a, A. R. (2009). A rubric for evaluating web-based learning environments. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 761-763.

Tips for Writing a Summative Evaluation Report

0 There is no “right” or “wrong” way to write a summative evaluation report. But there are good practices. I’ve prepared a list that summarizes what I’ve learned about evaluation reports, and some techniques for writing an effective one. In general, this list is mainly intended to help me, as these are points I thought were especially poignant and conducive to a good written report. The list is divided by suggested sections of the document.

There is no “right” or “wrong” way to write a summative evaluation report. But there are good practices. I’ve prepared a list that summarizes what I’ve learned about evaluation reports, and some techniques for writing an effective one. In general, this list is mainly intended to help me, as these are points I thought were especially poignant and conducive to a good written report. The list is divided by suggested sections of the document.

Summary

- This is the “condensed” version of your entire report. Write this section last, to give yourself time to mentally process and work through all the elements of your evaluation, and get a clear picture in your head of the most important points.

- Remember, some will only read the summary — and in many cases these may unfortunately be the key figures in the organization or among your stakeholders — so keep it concise. Preferably no more than two pages.

Introduction

- Remember who the stakeholders are, and for whom the report is being written. Target the introduction and only write what will interest them.

- Write the purposes for the evaluation. Answer questions like: “What did the evaluation intend to accomplish?” “Why was an evaluation necessary?”

- Write about the program being evaluated. Identify the origins of the program, objectives and goals, internal activities, technology used, successes, shortcomings, any staff members involved, and so on. This will make sure the evaluator understands what’s going on.

- Implicitly identify the evaluation model being used. This will be addressed in more detail in the next section.

- Briefly outline what will be covered in the rest of the report here.

Methodology

- Describe the sampling method(s) used. Who is the target population, and how was the sample randomized (if it was randomized)?

- Describe the evaluation model (goal-based, decision-making, discrepancy, etc.), and why it was chosen.

- Describe the data sources, and the instruments used to obtain the data. Explain the right tools for the job. If you gathered qualitative data, describe the interviews, observation, etc. and gathered nominal and ordinal data. If you gathered quantitative data, describe the measurements that gathered interval and ratio data. Include the specific measurement tools in appendices, if necessary.

- Describe the data analysis procedures used, such as statistical calculations and how scores were derived from the data.

- Keep graphs and charts to a minimum, as these will be presented in the next section.

Results

- Outline the objectives one by one, and describe how the program accomplished those objectives.

- Refer to the instruments used in the results, and make it clear which instruments were used to achieve which results.

- Descriptive and well-designed tables and charts are always nice. The more visually explanatory a table or chart is, the better, because it means you need less of a verbal description.

- Write the results only after all the data have been collected and organized into the visual displays, or analyzed for content.

- Describe the implications the results have for the targeted stakeholders.

- Make sure both positive and negative results are written. This may include cost/time/productivity benefits or disadvantages. Make sure any personal biases don’t skew the description of the results.

- Verify that the program actually caused the results, and that extraneous unanticipated factors did not contribute to the results.

Recommendations

- This section can act as both a conclusion as well as a place to put professional recommendations.

- Ensure that every objective and goal stated in the introduction is addressed.

- Although you made sure not to let your biases skew the results, you still have your own biases. Tactfully make clear your own biases in the report, and let the target readers know why your recommendations may differ from another evaluator’s. Justify your recommendations as best as possible, but make sure your unique perspective is clearly presented.

Evaluating BrainBlast

0 I’m getting close to wrapping up my reading of a rather interesting and insightful book: The ABCs of Evaluation (Boulmetis & Dutwin, 2005). It’s been an eye-opener for me, and has caused me to rethink how a lot of our professional development programs are evaluated.

I’m getting close to wrapping up my reading of a rather interesting and insightful book: The ABCs of Evaluation (Boulmetis & Dutwin, 2005). It’s been an eye-opener for me, and has caused me to rethink how a lot of our professional development programs are evaluated.

I’ve been writing a report about the survey results we collected last month at BrainBlast, our district’s annual technology conference. It’s a fantastic event that we put on every year in the summer. Up to 300 teachers and administrators attend the conference, participate in hands-on workshops, and win cool prizes. And every year we try to get good feedback about how the year’s conference went, by encouraging everyone to take a survey.

I started my report of BrainBlast 2010’s survey back in August, without realizing what I was doing was an evaluation report. However, I’ve since realized I made quite a few mistakes in my methodology, and I’ll probably need to start again from square one. For one, my evaluation was based largely on data that was improperly quantified. We collected some ordinal data in that we prompted each participant to rate their courses as Poor, Fair, Good, or Outstanding, but then I converted these to numerical quantities — 1 for Poor, 2 for Fair, 3 for Good, 4 for Outstanding — even though the division between each level is not necessarily equal. A lot of my report was based on this faulty assumption, and I made the same mistake a couple years ago in my comments about the BrainBlast 2008 survey. As a result I’ll need to reassess the data we collected this year.

In general, the survey we administered wasn’t really comprehensive and designed with a full-scale evaluation in mind, but I’ll do the best I can. Boulmetis & Dutwin (2005) outline a good format for writing evaluation reports, consisting of sections for a summary, evaluation purpose, program description, background, evaluation design, results, interpretation and discussion of the results, and recommendations. I think this is a good model to follow for any evaluations. At the very least it will be good practice for me as I hone my evaluation skills, and next year I’ll make sure I play a more important role in how we evaluate BrainBlast. Putting on BrainBlast is a significant financial investment for the district, albeit a very worthwhile one. It’s important that we make the most of how we conduct this valuable form of professional development.

References

Boulmetis, J., & Dutman, P. (2005). The ABCs of evaluation. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Evaluating Online Professional Development

0I’ve been musing over how to revise the online professional development offerings in our district for awhile. Our district is getting close to the point where we can start implementing changes that ensure meaningful learning. I’ve been studying different aspects of evaluations, namely the basics of how to conduct them and collect data.

A goal-based evaluation would be ideal for our online inservice. This type of evaluation measures efficiency (the timeliness in which the learning is conducted), effectiveness (whether the participants actually learned the material following the instruction), and impact (how their behavior is affected long-term). There is value to both qualitative and quantitative measurement tools, and the data we gather should consist of both.

It’s important to understand the stakeholders involved as well. I would like to tie our online inservice with curricular standards, particularly if any online learning is extended to students, and not just employees. We already allow our teachers to earn state CACTUS credit through our inservice portal, but I think without proper assessments the credit given does not demonstrate actual learning.

It’s strange that we have overlooked evaluation in a lot of our online professional development. It seems obvious now. We should set clear goals and objectives, outlining what we wish to accomplish. Evaluation should occur every step of the way, through both formative and summative assessments. Self-directed courses should be kept to a minimum, since it can be more difficult to collect formative assessment in this venue. In directed courses, the instructor can observe how the learners interact with the material, and take notes. I tend to favor project-oriented learning, so I don’t necessarily prefer quiz-based summative assessments. Final projects which effectively demonstrate all the material learned in the online class could be constructed instead, and assessed through a rubric. Another assessment, perhaps conducted through observation only, should also provide a means to determine the impact of the training one, three, or six months down the road. Has the material been applied to the participant’s instructional practices? Has their behavior changed? For example, if they participated in introductory blog training, are they now actively using their blog for instructional purposes and parent outreach?

Determining exactly how to form these assessments is what I’m still unclear about, and I still struggle with deciding how to form the questions in an evaluation, and knowing what to ask. I would like to focus more and get some practice determining and writing questions that lead to clear process descriptions and goal statements.