Standard 5: Evaluation

Candidates demonstrate knowledge, skills, and dispositions to evaluate the adequacy ofinstruction and learning by applying principles of problem analysis, criterion-referenced

measurement, formative and summative evaluation, and long-range planning.

An Evaluation of Moodle as an Online Classroom Management System

0I’ve finished an evaluation of how our district uses Moodle, and areas where we can improve. You can read the report below.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be releasing some follow-ups to this evaluation. Addendums, if you will. I was originally planning to supply personal assessments of each participating online course in the initial report, using a rubric for hybrid course design. After some thought I scratched this idea, because much of the rubric falls outside the scope of the district’s objectives for using Moodle, which were included in the report from the outset.

Instead, I will be delivering each a brief mini-report to teachers who participated in the survey (there were 17), with suggestions and recommendations stemming from a combination of the rubric and the survey assessments, tailored specifically to your courses and instruction.

There’s a few things I’ve learned, that I’ll have to remember for the next time we do an evaluation like this.

- Don’t underestimate your turn-out. I was expecting 100, maybe 200 survey participants tops. What I did not expect was receiving 800 survey submissions that I had to comb through and analyze. There were some duplicate data that had to be cleaned up as well, since a few of you got a little “click-happy” when submitting your surveys. I also had to run some queries on the survey database to figure out what some of the courses reported in the student survey actually were, since apparently students don’t always call their courses by the names we have in our system. Since this was a graduate school project, there was a clear deadline that I had to meet, and it was a little more than difficult to manage all that data in the amount of time I had. I should have anticipated that our Moodle-using teachers, being the awesome group they are, would actively encourage all their students to participate in this project. I will not make that mistake again.

- Keep qualitative and quantitative data in their rightful place. Although I provided graphs with ratings on each of the courses, I had to remind myself that these were not strict numerical rankings, as they were directly converted from Likert scaled questions. The degrees between “Strongly Disagree” and “Strongly Agree” are not necessarily the same in everyone’s mind, so when discussing results, one has to look at qualitative differences and speak in those terms. For example, if the collaboration “ratings” for two courses are 3.3 and 3.5 respectively, one can’t necessarily say that people “agreed more” with Course 2 than Course 1. There may be some tendencies that cause one to make that assumption, but one shouldn’t rely on the numerical data alone. To brazenly declare such a statement is hasty. If the difference had been significant, such as 1.5 vs. 4.5, then there would likely be some room for stronger comparisons.

- Always remember the objectives. When analyzing the data, it’s easy to get sidetracked with other interesting, but ultimately useful data. For example, a number of students and teachers complained about Moodle going down. This was a problem awhile ago, and it caused some major grief among people. However, it was not relevant to any of the objectives for the evaluation, even though it was tempting to explain/comment/defend this area. I take it personally when people criticize my servers! (Just kidding.)

- If the questions aren’t right, the whole evaluation will falter. Even though I had the objectives in mind when I designed the survey, I still found it difficult to know which were the right questions to ask. I’ve been assured that this aspect gets easier the more you do it. In the end, there was some extraneous “fluff” that I simply did not use or report on, because it wasn’t relevant (e.g. “Do the online activities provide fewer/more/the same opportunities to learn the subject matter?” My initial inclination was to include this in the Delivery, but when I finally looked at the finished responses, I realized it didn’t really fit anywhere and wasn’t relevant to any of the objectives.

Right now, being the lowly web manager that I am — and I only use the term “web manager” because “webmaster” is so 1990s; I don’t actually “manage” anyone — I don’t get many opportunities to do projects like this. But I’m aspiring to do more as a future educational technologist. Evaluations are more than just big formal projects … they underscore every aspect of what we as educators do. Teachers would do well to perform evaluations of their own instructional practices. When we add new programs or processes in our district, evaluations should accompany them. And as I complained in my mini-evaluation of BrainBlast 2010 a few days ago, all too often the survey data we gather just aren’t properly analyzed and used. We have some of the brightest minds in the state of Utah working in our Technical Services Department, but often we just perform “mental evaluations” and make judgments of the direction things should go, when we would do well to formalize the process, gather sufficient feedback, and use it to make informed decisions.

BrainBlast 2010 Survey Results

2 In the first week of August 2010 we wrapped up our 4th annual BrainBlast conference. It was quite a success. After 4 years, things tend to run a lot smoother at BrainBlast than they used to. According to most of the participants, the training was great, the keynote speakers were outstanding, and the food from Sandy’s was excellent. We did a few things differently this year. One big change is that we’re making a considerable push toward Moodle in our district, having already made it available to our teachers as an online classroom management system for the past 3 years. For BrainBlast 2010, we made sure almost every secondary teacher was enrolled in a Moodle session by providing enough sessions teaching this great tool. We’re also upgrading to Windows 7 in our district this year, and provided Windows 7 training to teachers in the first phase of the transition.

In the first week of August 2010 we wrapped up our 4th annual BrainBlast conference. It was quite a success. After 4 years, things tend to run a lot smoother at BrainBlast than they used to. According to most of the participants, the training was great, the keynote speakers were outstanding, and the food from Sandy’s was excellent. We did a few things differently this year. One big change is that we’re making a considerable push toward Moodle in our district, having already made it available to our teachers as an online classroom management system for the past 3 years. For BrainBlast 2010, we made sure almost every secondary teacher was enrolled in a Moodle session by providing enough sessions teaching this great tool. We’re also upgrading to Windows 7 in our district this year, and provided Windows 7 training to teachers in the first phase of the transition.

General Statistics

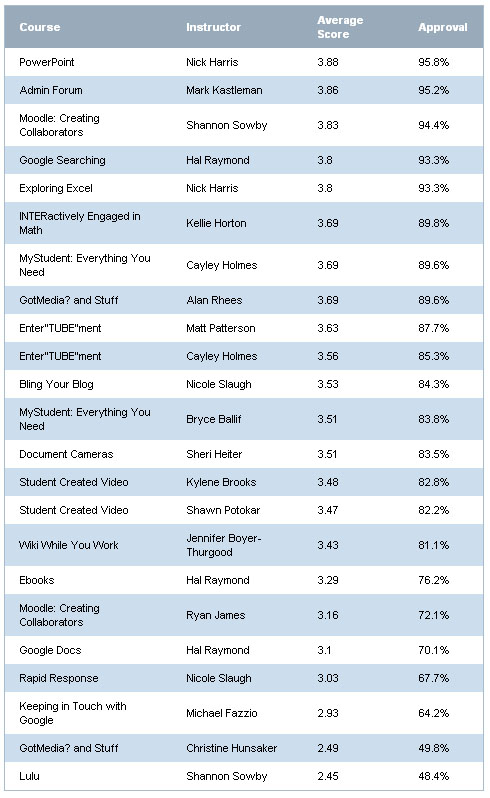

218 people participated in the survey. This number comprises 63% of the attendees, specifically 210 (70%) of the teachers, and 8 (18%) of the administrators. Table 1 indicates the highest-ranking courses, with the average scores for each on a scale of 1 to 4.

Table 1: Course Rankings and Approval

Mark Kastleman was a huge hit both in his first-day keynote session and the two follow-up sessions he held with the administrators. Barely outranked only by Nick Harris’ PowerPoint session, he delivered quite a dynamic keynote presentation about the relationship between the brain and learning. We were fortunate and appreciative that he and Mike King were able to share their insights at BrainBlast, and that Mark was able to provide follow-up sessions for the administrators.

This year we made sure to collect data on what people didn’t like about the conference. That was a major focus of the survey results, and we intentionally gathered negative feedback, which constituted most of the comments returned. We want to know what we’re not doing right. Constructive criticism will be one of the most helpful things to guide future BrainBlasts. The following information is not intended to be a “slam” against BrainBlast or anyone involved in organizing this excellent training event. Instead, I hope the comments prove helpful in optimizing and enhancing the learning experience for all BrainBlast participants. Some of the most common themes that popped up in the survey results are highlighted below.

Irrelevancy of the Classes

“I would have liked to actually been in the classes that I registered for. There were only two classes on my schedule that I wanted to be in. The others I did not register for, which was kind of annoying.”

“The hardest thing is when you are signed up for classes that you are not interested in at all. I have no desire to do Moodle and I was enrolled in the class for a second year in a row. Last year was fine, but this year I had no desire to listen. Is there a way we could let you know what classes we don’t want to take along with the ones we do?”

“Design [the] number of classes to accommodate number of students asking for them so you get the choices you want.”

“I felt that I was already pretty versed in [MyStudent] and didn’t learn anything new. I was not happy with having to take it over courses like Blogs!”

Many participants commented that they already knew the material in the classes they were selected for, or that they didn’t get any of the classes they wanted and that the material wasn’t relevant to them at all. This was an especially common concern in the Lulu class, as well as a few others. “It was not made clear how we would use the websites offered in [the Lulu] course,” one participant noted. “The online books seem too expensive to use in the classroom.” Another stated that Lulu “did not really apply to my curriculum.” “I didn’t really see the practical application of how I could use [Lulu] in class,” agreed yet another teacher. The common concern was that Lulu books tend to be too expensive for most parents.

A couple factors are directly related to the participants having been placed into classes not relevant to them:

- We did not collect much information at registration about teachers’ existing skill sets, let alone use this information to place teachers in classes that would be suitable for them.

- We did not use the wishlisted courses to determine how many sessions to offer. Last year, the average participant got 68% of the courses they wishlisted. This year, the participants only got 16%. The reason is this: When participants initially registered, they specified up to 6 courses they would like to take. They did this last year, too, except this year we did not delineate these courses by their track (elementary, secondary, or administrator). As a result, a lot of participants were wishlisting courses in tracks that would not be available to them. Elementary teachers were wishlisting courses in the secondary track, secondary teachers were wishlisting courses in the elementary track, and all teachers were wishlisting courses in the administrator track.

The bottom line is, we may as well have not even bothered with a wishlist, since it hardly determined which classes were assigned to whom.

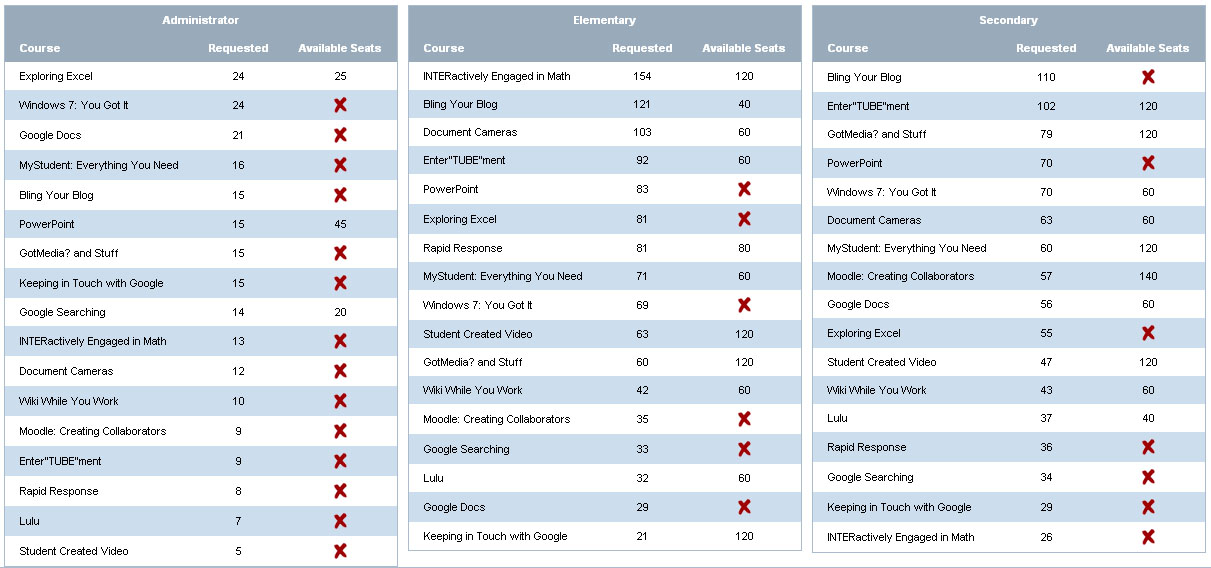

Table 2 indicates the preferred courses per track, as well as whether or not the course was even available in the track. The second column in each table shows the number of times the course was wishlisted during the initial registration, and the third column shows how many slots we actually provided for the course for the entire conference.

Table 2: Preferred Courses vs. Available Seats (click to enlarge)

Bling Your Blog! was one of the most requested classes (246 participants requested it), yet we only made room for 2 sessions (40 participants, or 16% of the requesters), and only in the elementary track. “I would have liked to attend a course on blogs,” remarked one teacher. “That was the one I wanted the most, but didn’t get to go to it.” “Please have a course on creating blogs for beginners,” begged another, “and have enough sessions [so] all who want it can have it.” Conversely, Lulu was one of the most unrequested classes. Only 76 requested it, yet we provided room for 5 sessions (100 participants). And we provided 6 sessions (120 participants) of Keeping in Touch with Google for elementary teachers, yet only 21 in the elementary track actually requested it! It’s hardly a surprise that these two ended up as some of the lowest ranking courses in the survey results, with so many disinterested people forced into them.

Recommendations for Improvement

Even if it means we need to open up BrainBlast registration earlier to allow for more planning time, we should consider the wishlisted classes and provide a suitable number of sessions to accommodate them. However, there is still value to a strictly randomized scheduling process. Teachers may attend classes they would not have normally requested due to an unfamiliarity with the material, but once they participate in the class they acquire new knowledge and skills directly relevant to their subject, classroom, and instructional strategies. At least, that’s one factor that has driven the design and development of BrainBlast. Every class should be relevant to everyone. Clearly, we did not accomplish that this year.

We should not discount the role a teacher’s general disinterest plays. If they simply don’t care about the subject material when they walk into the class, this preconception will carry all the way through, and stifle any engagement and learning they may experience. We need to find a way to identify which courses may be most relevant to a teacher, even if they don’t know it themselves. At the very least, a middle ground should be found between encouraging teachers to explore new technologies, and supplying the correct number of classes they specifically choose and feel are most relevant to them. As one teacher helpfully recommended, “Make sure that the courses are relevant to the participant . . . the majority of the courses were not very applicable to me. Plus, I only received 1 out of 6 courses that I had selected. The ones I had chosen would have been extremely relevant!”

Separation of Beginner and Advanced Classes

“It is frustrating to be in a course and want to learn more than you already know and it is based around the beginner.”

“Within the first part of the class I had things figured out, but we couldn’t move into more depth because there were other people in there that struggled.”

“Please, please, please have a beginners track and an advanced track. It is SO frustrating to not be able to learn anything new because the instructor runs out of time due to the fact there are people in the class that can’t even open the program they are talking about. ‘Wait! Slow down! How did you open Windows Movie Maker?!’ Very frustrating!”

“Some of the presenters tried to teach too much and I was way behind and couldn’t keep up.”

“Make a track that separates those who have little / no experience and those who have more experience and want to go deeper.”

The suggestion to divide classes by skill sets was very common this year. “Organize the classes by beginner, intermediate, advanced as well as by subject,” a teacher recommended. “It gets very frustrating to be in a class where the teacher is trying to explain a more complex subject and some of the students can’t even remember how to login or what the Internet icon looks like.” “I really feel that classes need to start being identified as beginner classes and classes for more advanced learners,” commented another. “A couple of the classes attended were not as helpful because they are skills I have learned at previous BrainBlasts.”

The suggestion to divide classes by skill sets was very common this year. “Organize the classes by beginner, intermediate, advanced as well as by subject,” a teacher recommended. “It gets very frustrating to be in a class where the teacher is trying to explain a more complex subject and some of the students can’t even remember how to login or what the Internet icon looks like.” “I really feel that classes need to start being identified as beginner classes and classes for more advanced learners,” commented another. “A couple of the classes attended were not as helpful because they are skills I have learned at previous BrainBlasts.”

This is not a bad suggestion, and there’s no denying that teachers attending BrainBlast have a wide range of abilities. Some come to the conference as technology experts, others as beginners, and this creates problems and negative feelings from different people in the classroom. “Have the instructors not wait for the one or two that don’t get it or are behind to catch up with the class,” recommended one teacher. “It really wastes time for those (the bulk of the class) that are ready to move to the next step.” The in-room techs should be able to help teachers catch up so the teacher doesn’t have to stop and wait, and perhaps we need to make that role more clear to them. However, it is rather difficult to create classes that appeal to everyone, when a few people are holding things back. It also creates a poor learning experience if some participants are constantly behind and relying on the school techs to assist them, just to keep up with the teacher.

Recommendations for Improvement

There is a need to organize classes into beginner and advanced, even if these are subdivisions within the elementary and secondary tracks. Our teachers have widely varied skill sets, and if we’re going to be randomly assigning them to classes, we shouldn’t operate under the assumption that “one class fits all.” Evaluating different technical skills is tricky, but well-crafted skill assessments should occur at registration time. At the very least, the random assignments should occur within subsets of designated beginner and advanced classes.

No More Shirts!

“Please get rid of the shirts and use that money for prizes.”

“If you must keep the shirt, make it a t-shirt. They’re cheaper.”

“Use the money spent on shirts to go towards equipment to be used in the classroom.”

“Give us more useful tech stuff. I would rather have had a tripod than a shirt.”

“No more shirts, they are atrocious and they are a waste of money.”

The general disdain for shirts was yet another common manifestation. I believe there is value to making BrainBlast shirts available to all who want it, but perhaps for next year participants could opt out of receiving a shirt when they register.

Other Ideas: Workshops

“I would like to have the option of being able to take the full two days to have a working workshop in Moodle,” suggested one teacher, “so that I can come away with tangible material that I can use in the classroom.” Day-long workshops are not uncommon to technology conferences, and some will provide this option, typically on an optional last day. Other times this is done during the regular conference schedule, so the participant enrolls in day-long workshops in lieu of a diversity of classes. Generally, the idea for BrainBlast has been to provide a good range of classes to expose teachers to multiple technologies, and to set aside workshop-oriented instruction for E-volve and iLead classes. However, many participants mentioned that the class time was too short to reasonably cover the material:

“I would like to have the option of being able to take the full two days to have a working workshop in Moodle,” suggested one teacher, “so that I can come away with tangible material that I can use in the classroom.” Day-long workshops are not uncommon to technology conferences, and some will provide this option, typically on an optional last day. Other times this is done during the regular conference schedule, so the participant enrolls in day-long workshops in lieu of a diversity of classes. Generally, the idea for BrainBlast has been to provide a good range of classes to expose teachers to multiple technologies, and to set aside workshop-oriented instruction for E-volve and iLead classes. However, many participants mentioned that the class time was too short to reasonably cover the material:

“Most of the classes went by too fast, especially on wikis. I had never even heard of one and there was just not enough time to really understand.”

“Make more ‘beginning level’ classes available and expand time on some of the sessions so we have more time to ‘create’ or to produce a finished product.”

“Some classes need to spend more time on basics. Go deep instead of broad.”

“Got Media & Stuff was the weakest because it contained so much info and not enough time to explain about each site.”

“Student Created Video would have been better if there was enough time. The time was cut short due to the general session going over a bit.”

“Could have used more time in Bling My Blog….and Google…”

Whether or not longer, focused workshops would incorporate well into BrainBlast remains to be determined. With our training efforts, it would probably be more suitable to divide workshop-based courses into other training venues, such as E-volve or iLead.

Other Ideas: Virtual BrainBlast

“It would be nice to have this more than once a year,” suggested another teacher. I’m reminded of FETC, which is one of the largest annual educational technology conferences in the U.S. Most educators are probably familiar with it, but many do not know that they also host Virtual FETC conferences a couple times throughout the year. The online version of FETC is portrayed in a virtual web-based environment with INXPO’s Virtual Events & Conferences. Participants can travel around the virtual conference setting, viewing products and communicating with vendors in real-time, collecting virtual memorabilia, taking notes, and interacting with other educators online. Sessions are broadcast at set times, typically chosen from archived recordings of the last FETC, though live streams are possible, too. During the sessions, participants can, and are even encouraged to chat amongst each other about the topic being presented. Some have claimed that the best learning during a conference happens before and after the sessions, when everyone networks together to talk about what was learned, explore how they can apply the new information, and share their own insights to a group of eager-to-listen professionals in their field. Collaboration is a hugely beneficial aspect of any conference, and virtual conferences are ideal for this form of collaboration. Many participants can gather together in the same room, more than would be possible in a physical setting, and have the opportunity to collaborate with the group in a way that might not be as easily accomplished at a large meeting of educators.

“It would be nice to have this more than once a year,” suggested another teacher. I’m reminded of FETC, which is one of the largest annual educational technology conferences in the U.S. Most educators are probably familiar with it, but many do not know that they also host Virtual FETC conferences a couple times throughout the year. The online version of FETC is portrayed in a virtual web-based environment with INXPO’s Virtual Events & Conferences. Participants can travel around the virtual conference setting, viewing products and communicating with vendors in real-time, collecting virtual memorabilia, taking notes, and interacting with other educators online. Sessions are broadcast at set times, typically chosen from archived recordings of the last FETC, though live streams are possible, too. During the sessions, participants can, and are even encouraged to chat amongst each other about the topic being presented. Some have claimed that the best learning during a conference happens before and after the sessions, when everyone networks together to talk about what was learned, explore how they can apply the new information, and share their own insights to a group of eager-to-listen professionals in their field. Collaboration is a hugely beneficial aspect of any conference, and virtual conferences are ideal for this form of collaboration. Many participants can gather together in the same room, more than would be possible in a physical setting, and have the opportunity to collaborate with the group in a way that might not be as easily accomplished at a large meeting of educators.

Virtual conferences are not unusual. Second Life is another popular platform for delivering virtual conferences such as Virtual Worlds: Best Practices in Education (WBPE), SLanguages, UNC: Teaching and Learning with Technology, SLACTIONS, and others. While I wouldn’t advocate opening up Second Life to all teachers inside the district (not at this point, at least), this could be a viable platform for a virtual BrainBlast. But on the other hand, a virtual BrainBlast wouldn’t need to be so sophisticated. Just gathering teachers in a basic web-based environment where they can communicate and participate in great training has tremendous benefits. And it would be a considerably more cost-effective supplement to BrainBlast than the summer event at Weber High School.

Evaluating Learning

One obvious question we may be overlooking is, “How well do we assess the learning of the participants?” BrainBlast is designed to be a highly constructionist, hands-on learning experience. Every classroom is equipped with a computer lab, and during the sessions the participants are expected to produce concrete artifacts and gain both conceptual and procedural knowledge of specific technology tools. Yet no official learning evaluation process is in place that I’m aware of. At the very least, the instructors and school techs stationed in each room should take notes during or after the training sessions of the overall learning experience, common problems that arose, and answer questions regarding the effectiveness of the session. The direct observation would prove invaluable in determining which instructional strategies do and do not work.

There are three particular aspects we should measure in any evaluation: efficiency, effectiveness, and impact. BrainBlast is undeniably efficient: all participants are given a wide range of training within a 12-hour timeframe over 2 days. The effectiveness is a little more debatable. Do all participants leave the sessions knowing the material they were supposed to learn? Are there always clear objectives in each class that should be accomplished by each participant? While we don’t want participants to take a grueling multiple choice quiz at the end of each session to determine if they actually learned anything, we can assess their learning by viewing their completed artifacts.

However, does BrainBlast actually have an impact? After a teacher takes a blogging class at BrainBlast, do they become an active blogger throughout the school year? If a teacher receives training on using Flip Video cameras, do they start using this in their class, and finding ways to engage students with video creation? 140 secondary teachers received training in Moodle. And now, a few months later, we still only have about 30-40 teachers actively using our Moodle system. This is about the same number of teachers that were using Moodle last year. Did BrainBlast actually have an impact on Moodle usage?

Granted, we shouldn’t expect teachers to use all the educational technology tools they have learned about in their daily instruction, but currently we do not formally measure if teachers are using what they learned a month, three months, or six months after the event. From past experience, and having received the most basic questions on how to blog, upload WeberTube videos, use a document camera, etc. from teachers that knowingly have participated in BrainBlast’s related training venues, the effectiveness and impact of BrainBlast needs to be determined.

Where is Social Bookmarking?

![]() I commented on this topic 2 years ago after BrainBlast 2008. Classes on social bookmarking have been strangely absent from BrainBlast’s course offerings. Since 2007, Delicious, the most popular social bookmarking tool, has been consistently ranked as the top #1 and #2 most useful tools for learning by the Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies, which gathers data and feedback from educators all over the world. Why is social bookmarking such an important tool for teachers? There are numerous educational resources on the web, and social bookmarking is the most popular and effective way for teachers to share them amongst each other. It’s not just ordinary things like math manipulatives or quiz sheets that are shared, but links to videos, podcasts, desktop applications, helpful teacher blogs, educational trends, and bleeding-edge teaching ideas. The worldwide teacher network is opened up through social bookmarks, and our teachers can tap into this learning network by taking their bookmarks online.

I commented on this topic 2 years ago after BrainBlast 2008. Classes on social bookmarking have been strangely absent from BrainBlast’s course offerings. Since 2007, Delicious, the most popular social bookmarking tool, has been consistently ranked as the top #1 and #2 most useful tools for learning by the Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies, which gathers data and feedback from educators all over the world. Why is social bookmarking such an important tool for teachers? There are numerous educational resources on the web, and social bookmarking is the most popular and effective way for teachers to share them amongst each other. It’s not just ordinary things like math manipulatives or quiz sheets that are shared, but links to videos, podcasts, desktop applications, helpful teacher blogs, educational trends, and bleeding-edge teaching ideas. The worldwide teacher network is opened up through social bookmarks, and our teachers can tap into this learning network by taking their bookmarks online.

Saving social bookmarks is as easy as installing the Delicious add-on in your browser and clicking Save. It’s no more complicated than clicking “Add to Favorites” in Internet Explorer. Plus, you can access your bookmarks from any computer, so you don’t have to panic when you realize that cool link to the video you wanted to show your class was bookmarked on your home computer, but not your work computer. Social bookmarking is such an invaluable asset. No longer do you have to hunt for your own resources for your classroom lessons, but you can tap into the research that thousands of other teachers have done and find existing links that others have shared. New links can be emailed to you daily, or you can subscribe to RSS feeds of bookmarks shared by different users, or bookmark groups that are created around topics. 99% of Weber School District’s Links of the Day come from Delicious and Diigo (another popular social bookmarking service which has some great extra features like highlighting and annotating pages). And about 99.9% of the links that get sent to my inbox are never put up on the Links of the Day page, so it would be beneficial if teachers have access to these other links themselves.

The bottom line is this: Our teachers are going to a technology conference, to learn about tools for learning and teaching. They are sitting in computer labs and learning about great web sites. But what do they do when they want to save these links? They whip out their notebooks and pens and write them down. These could easily be saved with a simple click and the teacher could access it later from any computer. The final step in the process is absent. All the BrainBlast links could even be merged into a shared bookmark group that anyone, anywhere can access for future reference. It’s rather strange that one of the top tools for learning has never even been mentioned at BrainBlast.

Conclusion

Overall, participants were quite happy with how the conference played out. There is clearly some room for improvement, particularly in ensuring the classes are relevant to everyone, and taking unique skillsets and aptitudes into account when the participants’ classes are assigned. We must improve our evaluation procedures as well, and pay careful attention to collecting good, reliable data if we are to determine how best to improve this event. There may be some value to including an online venue to supplement BrainBlast, and making sure that all the materials are easily accessible at a later date.

And finally, the best suggestion we received from the survey:

Analyzing the Problem

0 We solve problems every day. Sometimes the problems are simply figuring out where you left your car keys. Other times, it’s determining the best way to reach the unique needs of your students. Often we solve these problems without really thinking through the process. We just mentally “connect the dots” and arrive at conclusions. The conclusions may not necessarily be the best ones, or we may not always explore all the options at hand. In most cases, for mundane tasks, it’s not really necessary. When you can’t find your car keys in one location, you naturally move on to another until they’re located. But some situations may warrant a more in-depth analysis of the problem.

We solve problems every day. Sometimes the problems are simply figuring out where you left your car keys. Other times, it’s determining the best way to reach the unique needs of your students. Often we solve these problems without really thinking through the process. We just mentally “connect the dots” and arrive at conclusions. The conclusions may not necessarily be the best ones, or we may not always explore all the options at hand. In most cases, for mundane tasks, it’s not really necessary. When you can’t find your car keys in one location, you naturally move on to another until they’re located. But some situations may warrant a more in-depth analysis of the problem.

Analyzing a problem is the intermediary step between recognizing the problem and arriving at a solution, and it involves using data collection and forming decision-making strategies. Defining clear goals and objectives is important, too. For BrainBlast 2010 last summer, we had all the attendees participate in a survey on the final day of the conference. The goal was to collect data to enhance the quality of instruction for future conferences, and we collected some valuable information to this end, through a combination of Likert scale questions, and prompted constructive criticism. With these data, we can form the necessary decisions to improve future BrainBlasts, and avoid repeating any mistakes we made in the past.*

An evaluator must assess aspects such as the needs of the program and its users. It’s important to be aware of the different data-collection tools at one’s disposal as well. My own forthcoming Moodle evaluation will be largely interview-based, with some backend data collection assessing general academic performance averages and usage of online course activities. Interviews in particular are useful formative evaluation tools. It’s important to not neglect formative evaluation during a program, as it can reveal scenarios, ideas, and possible venues for improvement before the conclusion.

Objectivity is important as well when analyzing a problem. After all, if an evaluation isn’t objective and free of bias, it is worthless. While it’s likely not possible that an evaluator can completely cast their biases aside, especially when offering professional recommendations, it’s important they make every effort to do so. Also, detailing the steps the analysis took and the efforts to collect objective data goes a long way.

* An analysis of the BrainBlast 2010 survey results will be posted in a few days. (Update: survey results are now available.)

The Case for Ed Tech

0“I can’t believe you let students access the Internet without even talking to us parents about it. I don’t see why they need to be online. We didn’t have these things when we were in school and we got a good education. Kids are just wasting their time online on websites like Myspace and schools are doing nothing about it. How about you use the taxpayer money you waste on expensive computers to fix up the schools or pay the teachers more?”

This is just one of many messages that I’ve received from parents who are upset about the fact that our schools use technology. With a career in educational technology and having tinkered with computers since the age of seven, I sometimes find these statements foreign and quite confusing. It’s not uncommon to find parents who think schools are wasting their time buying new computers, and many of them have never even heard of an interactive whiteboard or a document camera. However, it’s a perfectly valid concern. They have good intentions. They believe education should come first, but it may not be readily apparent just how technology improves the quality of education. If we as educators are making decisions to adopt additional technology, the justification for its use rests on our shoulders. Fortunately, there is a wide body of evidence that demonstrates the powerful and beneficial impact technology can have on an educational environment.

What is Educational Technology?

So there’s no ambiguity, let’s define exactly what is meant by “educational technology.” According to the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT), it is “the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources” (Januszewski & Molenda, 2008, p. 2). What this means in a nutshell is that educational technology exists specifically to help students become better learners. If it does not help them in this capacity, it is not an appropriate technology.

So there’s no ambiguity, let’s define exactly what is meant by “educational technology.” According to the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT), it is “the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources” (Januszewski & Molenda, 2008, p. 2). What this means in a nutshell is that educational technology exists specifically to help students become better learners. If it does not help them in this capacity, it is not an appropriate technology.

Insisting we shouldn’t be using technology in a school is like saying we shouldn’t be driving cars because we have perfectly good horses. There are things a car can do that a horse can’t, such as travel 80 miles per hour and get people to their destinations faster. On the other hand, a horse can travel on rugged terrain most cars can’t reach.

Perhaps it’s ironic that the parent who sent the complaint did so through email. Why was email used instead of the traditional postal service? Because modern technology advances allow near-instantaneous communication across the world, and since my email address was readily available to this parent, it was the obvious choice. It was the best tool for the job, just like depending on the situation, a car or horse may be the best means of transportation.

A proper study of educational technology identifies the best tools that will create optimal learning experiences for students, or benefit teachers in some way that helps them communicate their instruction more efficiently and effectively. One important fact should be kept in mind: Technology is not a replacement for a teacher. There is no time in the foreseeable future when a teacher’s job will be made obsolete. Instead, when placed in the hands of a good teacher, technology can improve teaching skills and cultivate an improvement in students’ learning.

Technology Transforms the K-12 School System

Most of our students are already immersed in a technological world. They’re skilled users who have grown up with technology in their daily lives. They’re users of cell phones, iPods, video games, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and many other technology tools. Prensky (2001) refers to these children as “digital natives,” young people who are adept users of technology and have always been surrounded by it. They are familiar and competent with the digital tools, and embrace new technologies as they appear. Contrasted with “digital natives” are the “digital immigrants,” the older generation who recall a time when modern technology tools did not exist, and who often have an awkward time adopting them. Students today have different expectations of technological engagement than students used to, and they may expect the same level of engagement in their schools.

Most of our students are already immersed in a technological world. They’re skilled users who have grown up with technology in their daily lives. They’re users of cell phones, iPods, video games, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and many other technology tools. Prensky (2001) refers to these children as “digital natives,” young people who are adept users of technology and have always been surrounded by it. They are familiar and competent with the digital tools, and embrace new technologies as they appear. Contrasted with “digital natives” are the “digital immigrants,” the older generation who recall a time when modern technology tools did not exist, and who often have an awkward time adopting them. Students today have different expectations of technological engagement than students used to, and they may expect the same level of engagement in their schools.

Fortunately, there is a wide spectrum of technology tools that can benefit learning in a K-12 environment. For example, teachers can use podcasting to improve their students’ reading, literacy, and language skills, and use auditory playback to identify where they need additional instructional assistance. Podcasting can also be used to share lectures that students may have missed (Hew, 2009). Document cameras and digital projectors allow teachers to display papers, photographs, books, and lab specimens on a big screen (Doe, 2008). Google Earth allows students to instantly explore the world, locate famous landmarks, and watch embedded instructional videos. Blogs allow both students and parents to instantly communicate with the teachers, and provide a window into the classroom. When used by students, they can increase literacy skills and promote global citizenship (Witte, 2007). Augmented reality devices project images over real-life objects, creating visual, highly-engaging activities (Dunleavy, Dede, & Mitchell, 2007). Even the video games students like to play online have educational promise because “they immerse students in complex communities of practice” and “invite extended engagement with course material” (Delwiche, 2006). Our youngest learners can benefit from technology, too, as one study showed that preschoolers who were introduced to video and educational games experienced marked improvement in literacy and conceptualizing skills over students who did not have access to these technology tools (Penuel, Pasnik, Bates, Townsend, Gallagher, Llorente, & Hupert, 2009).

Students with disabilities also benefit from using technology tools. Rhodes & Milby (2007) found that students with disabilities are often proficient with using technology to accomplish learning tasks and interactive activities they wouldn’t otherwise be able to do. Electronic books, with their text-to-speech capabilities, animation, and interactivity can boost their confidence, and encourage fluency, comprehension, and language skills.

Technology is more than just a gimmick. It can improve the cognitive learning abilities of students, and support and enhance their learning capabilities (Krentler & Willis-Flurry, 2007). Even students who generally struggle with learning or have disciplinary problems show improvement when technology is used (Dunleavy, et al., 2007). Technology can stimulate children’s cognitive development by improving logical thinking, classification, and concept visualization skills, and creating intellectually stimulating hands-on learning activities. Skills such as literacy, mathematics, and writing are improved and reinforced by a technology-oriented education (Mouza, 2005). Students who recognize technology’s educational benefits are more likely to become engaged in the learning process, seek out their own learning opportunities, maintain a stronger focus on accomplishing their learning tasks, and improve their higher-order thinking skills that allow them to become better problem-solvers (Hopson, Simms, & Knezek, 2001).

One benefit of the Internet is that students have an easy way to share their hard work with a wide audience. Students gain confidence and pride when they see their products in a visual form. The online social aspect can also reduce feelings of isolation, and encourage discussions and peer instruction (Mouza, 2005). One researcher commented, “Youth could benefit from educators being more open to forms of experimentation and social exploration that are generally not characteristic of educational institutions” (Ito, Horst, Bittanti, Boyd, Herr-Stephenson, & Lange, 2009). So important is technology to a K-12 school environment that the National Association for the Education of Young Children states that technology should be used as an active part of the learning process (Rhodes & Milby, 2007).

Technology Enhances Professional Development

Professional development refers to any skills or knowledge obtained that benefits one in their career. We are experiencing an unusual phenomenon in our school systems. For once, most of our students possess a greater knowledge and skill in a field than many teachers do. It’s important that teachers engage in professional development opportunities so they can “keep up” with the students’ extensive experience with technology.

Professional development refers to any skills or knowledge obtained that benefits one in their career. We are experiencing an unusual phenomenon in our school systems. For once, most of our students possess a greater knowledge and skill in a field than many teachers do. It’s important that teachers engage in professional development opportunities so they can “keep up” with the students’ extensive experience with technology.

Not long ago, the extent of a teacher’s learning didn’t stretch beyond the walls of the school. Teachers would gather in the teachers’ lounge to discuss their instructional strategies. One way to motivate teachers and provide ongoing work-related educational support is through online communities, where peers support each others’ learning. Hausman and Goldring (2001) found that teachers are most committed to their schools when they have a sense of community, and are offered opportunities to learn.

In an online community, a teacher can post a question and receive back insightful answers with minimal effort on their part. Teachers can also share their experiences, and gather evidence of the success of new techniques (Duncan-Howell, 2010). Online courses are prevalent, podcasts are available to extend learning, professional-oriented chat rooms spring up, educators share their thoughts on their blogs, and teachers set up and share webcam feeds at conferences so other members of the online community can learn the new techniques and skills necessary for teaching modern students. Technology has allowed teachers to figuratively break through the walls of their schools and engage a vast community of like-minded individuals who come together to interact, learn, and share knowledge with each other.

Technology is Necessary in the Outside World

One of the expectations of our education system is that students will be taught the skills necessary to be productive and competitive members of society and the modern workplace. As Harris (1996) pointed out, “Information Age citizens must learn not only how to access information, but more importantly how to manage, analyze, critique, cross-reference, and transform it into usable knowledge” (p. 15). Businesses are rapidly adopting new technologies to simplify and enhance their processes, and are demanding higher-order critical thinking skills of their job candidates. Adults who use the Internet have greater success at obtaining jobs, and have higher salaries (DiMaggio, Hargittai, Celeste, & Shafer, 2004), and technology prepares students for the modern-day jobs they will obtain by teaching them skills such as motivation, engagement, and online collaboration (Ringstaff & Kelley, 2002). If students are not taught the necessary skills they need during their K-12 education, they will be at a severe disadvantage when they are ready to enter the workforce.

One of the expectations of our education system is that students will be taught the skills necessary to be productive and competitive members of society and the modern workplace. As Harris (1996) pointed out, “Information Age citizens must learn not only how to access information, but more importantly how to manage, analyze, critique, cross-reference, and transform it into usable knowledge” (p. 15). Businesses are rapidly adopting new technologies to simplify and enhance their processes, and are demanding higher-order critical thinking skills of their job candidates. Adults who use the Internet have greater success at obtaining jobs, and have higher salaries (DiMaggio, Hargittai, Celeste, & Shafer, 2004), and technology prepares students for the modern-day jobs they will obtain by teaching them skills such as motivation, engagement, and online collaboration (Ringstaff & Kelley, 2002). If students are not taught the necessary skills they need during their K-12 education, they will be at a severe disadvantage when they are ready to enter the workforce.

Face-to-face communication skills are and likely always will be important in the workplace, but social business skills have expanded to include more than just face-to-face communication. Teleconferencing, collaborative document authoring, online correspondence, video conferencing, and more are common in modern workplaces. While parents think their children are wasting their time talking to others online, our youth are acquiring basic social and technological skills they need to fully participate in contemporary society (Ito, et al., 2009). If we restrict our children from using these online social forms of learning, we are stifling their future careers, and preventing them from being able to compete in this digital age.

Conclusion

In the parent’s message at the beginning of this paper there was one fundamental misconception: that technology and learning are at odds with each other. This is simply not the case, and the research paints a very different picture. We are experiencing a “shrinking world” as technology has opened lines of communication that just 20 years ago were either impossible or a monumentally expensive feat. Students should realize the educational potential of technology, and we must be prepared to create learning opportunities that encourage them to use technology in their education. Ultimately, if we wish to create motivated, lifelong learners with the necessary knowledge and skills that give them a competitive advantage in modern careers, we must embrace technology in our schools.

References

Delwiche, A. (2006). Massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) in the new media classroom. Educational Technology & Society, 9(3), 160-172.

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., & Shafer, S. (2004). From unequal access to differentiated use: A literature review and agenda for research on digital inequality. Social inequality, 355–400.

Doe, C. (2008). A look at document cameras. MultiMedia & Internet@Schools, 15(5), 30-33.

Duncan-Howell, J. (2010). Teachers making connections: Online communities as a source of professional learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 324-340. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00953.x

Dunleavy, M., Dede, C., & Mitchell, R. (2009). Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. Journal of Science Education & Technology, 18(1), 7-22. doi:10.1007/s10956-008-9119-1

Harris, J. (1996). Information is forever in formation, knowledge is the knower: Global connectivity in K-12 classrooms. Computers in the Schools, 72(1-2), 11-22.

Hausman, C. S., & Goldring, E. B. (2001). Sustaining teacher commitment: The role of professional communities. Peabody Journal of Education, 76(2), 30-51.

Hew, K. (2009). Use of audio podcast in K-12 and higher education: A review of research topics and methodologies. Educational Technology Research & Development, 57(3), 333-357. doi:10.1007/s11423-008-9108-3

Hopson, M. H., Simms, R. L., & Knezek, G. A. (2001). Using a technology-enriched environment to improve higher-order thinking skills. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 34(2), 109-120.

Januszewski, A., & Molenda, M. (2008). Educational technology: A definition with commentary. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum, Inc.

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittanti, M., Boyd, D., Herr-Stephenson, B., & Lange, P. G. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. Retrieved May 4, 2010, from http://digitalyouth.ischool.berkeley.edu/files/report/digitalyouth-WhitePaper.pdf.

Krentler, K. A. & Willis-Flurry, L. A. (2005). Does technology enhance actual student learning? The case of online discussion boards. Journal of Education for Business, 80(6), 316-321. doi:10.3200/JOEB.80.6.316-321

Mouza, C. (2005). Using technology to enhance early childhood learning: The 100 days of school project. Educational Research & Evaluation, 11(6), 513-528.

Penuel, W. R., Pasnik, S., Bates, L., Townsend, E., Gallagher, L. P., Llorente, C., & Hupert, N. (2009). Preschool teachers can use a media-rich curriculum to prepare low-income children for school success: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Summative evaluation of the “Ready to learn initiative”. Education Development Center. Retrieved May 4, 2010 from http://cct.edc.org/rtl/pdf/RTLEvalReport.pdf.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5). Retrieved May 4, 2010, from http://www.hfmboces.org/HFMDistrictServices/TechYES/PrenskyDigitalNatives.pdf

Rhodes, J., & Milby, T. (2007). Teacher-created electronic books: Integrating technology to support readers with disabilities. Reading Teacher, 61(3), 255-259.

Ringstaff, C., & Kelley, L. (2002). The learning return on our education technology investment: A review of findings from research. San Francisco: WestEd. Retrieved May 4, 2010, from https://www.msu.edu/~corleywi/documents/Positive_impact_tech/The%20learning%20return%20on%20our%20educational%20technology%20investment.pdf

Witte, S. (2007). “That’s online writing, not boring school writing”: Writing with blogs and the talkback project. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(2), 92-96.

Technology Use Planning Presentation

0Below are some presentation slides I coauthored with two of my classmates. The topic is designing a Technology Use Plan.

Gaming is an activity enjoyed by many students, and when used for educational purposes, games can improve student motivation towards learning, particularly when used in the creation of constructivist learning opportunities. Applying constructivist principles to educational game-based learning activities yields an approach that puts students in the role of active learners and content creators.

Gaming is an activity enjoyed by many students, and when used for educational purposes, games can improve student motivation towards learning, particularly when used in the creation of constructivist learning opportunities. Applying constructivist principles to educational game-based learning activities yields an approach that puts students in the role of active learners and content creators. A few months ago, I co-founded a project called Digital Parent with a few other educators across North America. The goal of Digital Parent is to deliver technology workshops for parents. The basic idea is to help parents better understand technology, and provide training that will benefit them as they seek to understand the benefits of educational technology, as well as technology tools relevant to their personal lives. The project is still in its formative stages, and although we’ve been on hiatus for awhile, I’m hoping with this new instructional project I’ve designed we can get the project moving again.

A few months ago, I co-founded a project called Digital Parent with a few other educators across North America. The goal of Digital Parent is to deliver technology workshops for parents. The basic idea is to help parents better understand technology, and provide training that will benefit them as they seek to understand the benefits of educational technology, as well as technology tools relevant to their personal lives. The project is still in its formative stages, and although we’ve been on hiatus for awhile, I’m hoping with this new instructional project I’ve designed we can get the project moving again.